Concussions in children: Study led by UNE medical student shows different paths to recovery

Concussions in adults and young athletes have received a great deal of attention, both in the media and in research. But a new study from University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine student Kaitlyn Chin focuses on a population getting far less attention: children who suffer from non-sports-related concussions.

“Concussions are common among children, yet the literature is limited with regard to understanding trajectory of recovery after concussion, particularly in children with non-sports related injuries and for younger children,” Chin explains.

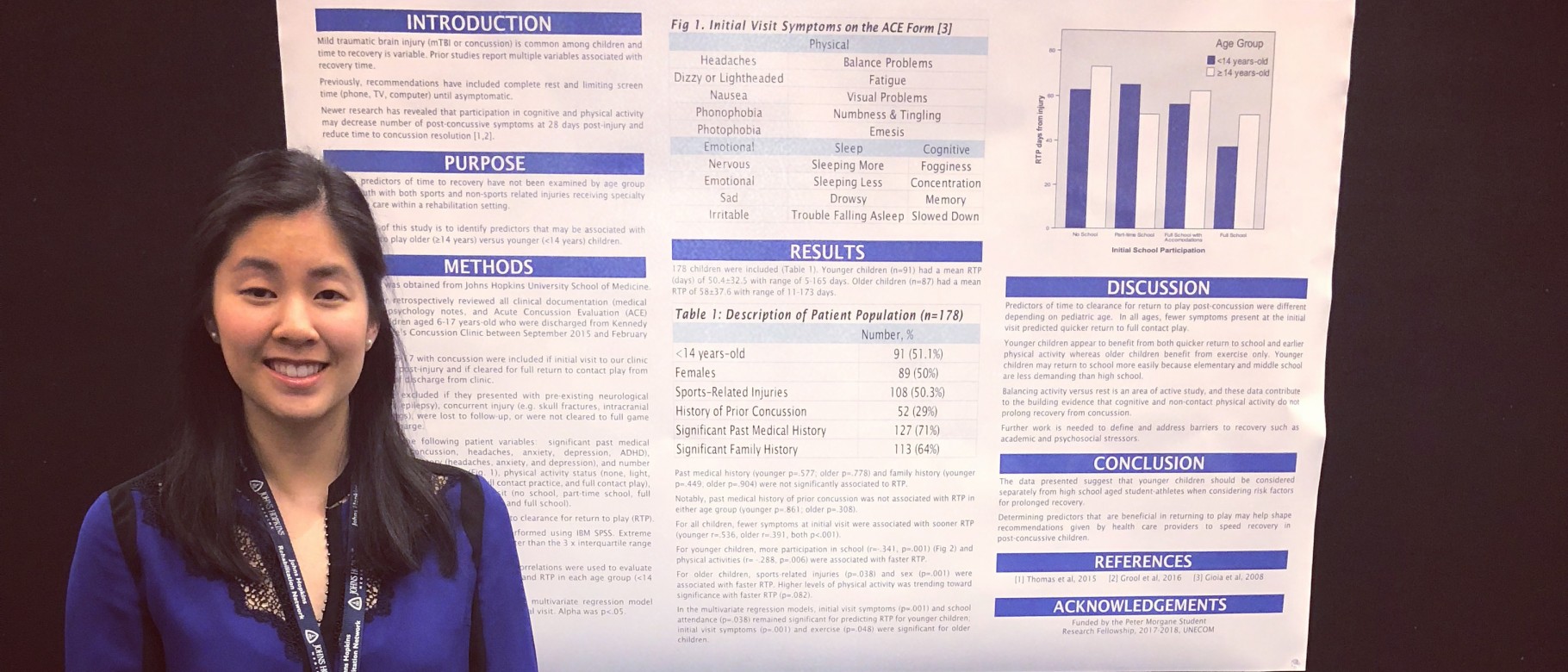

Chin’s abstract was published in the American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation and presented at the Association of Academic Physiatrists (AAP) Annual Meeting in Atlanta, Georgia. Chin, a second-year student at UNE COM, has a background in orthopedic research and a passion for sports medicine and Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. When she discovered the Concussion Clinic at the Kennedy Krieger Institute, which is affiliated with Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, she knew it would be an ideal place to conduct research. She and her team examined the medical records of 178 children, ages six to 17 years old, who were treated for concussion in this academically-affiliated, rehabilitation-based clinic and who were medically cleared to return to play between September 2015 and February 2017. A Peter Morgane Research Fellowship award provided support for the project.

The researchers reviewed each child’s record noting when they were approved to return to play. Then, they looked at several other factors for each child, including: sex, cause of the concussion (i.e., sports or non-sports-related), number of symptoms, school attendance and exercise status at the initial visit to the clinic. Finally, they considered these factors when the children were placed into two different categories – children under 14 years and children over 14 years – to see if there are any differences based on age.

“We were looking at several different factors to see how they impacted a child’s recovery,” says Chin. “Our hope is to identify modifiable factors that may help shape future recommendations given by health care providers to speed recovery.”

Chin’s team found the number of symptoms affected how quickly all children were cleared to return to play – with fewer symptoms being associated with a faster return to play. For older children, male sex and higher level of exercise during recovery were both associated with a faster return to play. For younger children, higher levels of both exercise and school participation, such as attending class, completing homework and tests, were associated with faster return to play.

Overall, the study suggests that elementary and middle school aged children should be considered separately from high-school-aged students when considering risk factors for prolonged recovery from a concussion. Furthermore, Chin’s team found that school participation and non-contact exercise were not harmful and did not prolong recovery.

“Our study adds to the literature supporting that return to cognitive and safe physical activities while a child is still recovering from concussion does not prolong time to recovery,” says Chin of the findings. “Every child is different, and recovery is different for each concussion. To that end, a concussion recovery plan should be tailored for each child, and parents should seek help from the child’s pediatrician or other medical professionals for guiding care after a concussion.”

Chin says she hopes to see the research continue through prospective studies that lead to a better understanding of how timing and type of physical activity contribute to recovery after concussion, as well as how to best assess and address barriers to recovery such as the stress associated with returning to school. She says her experience at the Kennedy Krieger Institute reinforces her desire to pursue PM&R and to continue research as a physician. “At Kennedy Krieger Institute, I was exposed to the pediatric limb deficiency clinic. That experience has inspired me to incorporate patients with limb deficiencies into my future sports medicine practice.”

Chin is thankful for the support of her mentor at Kennedy Krieger Institute, Stacy Suskauer, M.D. “This experience gave me a sense of what it’s like to be a physician researcher. The field of medical research is about innovating new treatments and continuing to improve quality of care, and I am fortunate to be a part of this.”

Read more about the research from the Association of Academic Physiatrists and MD Edge.

To learn more about the University of New England’s College of Osteopathic Medicine, visit www.une.edu/com

To apply, visit www.une.edu/admissions