UNE’s intrepid endeavor to carry out research through COVID-19

It was a day that most among the University of New England community vividly remember: March 13, 2020, the day the difficult decision was made to move nearly all undergraduate and graduate programming online as a novel virus swept its way across the nation. Amid a sea of unknowns — including, at the time, how events such as Commencement could be held and when students would return to campus — was a lingering question: for an institution that prides itself on research, how and when could faculty and student scientific exploration continue?

When that fateful day came, most research operations at the University were ceased, much as they were at colleges and universities across the globe. It was a difficult feat to execute: experiments had been ongoing for months; research animals still had to be cared for; and remote learning had made real-time scientific inquiry virtually impossible.

Compounding the chaos was ever-shifting public health guidance from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Maine CDC, Office of Governor Janet Mills, and UNE’s own public health and medical experts.

Troubleshooting the Unknown

As the virus began to spread across the U.S. and Maine, an all-hands-on-deck effort ensued to limit the number of people in laboratories, find alternative modes of research for students, and keep essential operations flowing.

“We went into emergency operations mode,” said Karen Houseknecht, Ph.D., professor of pharmacology and associate provost for Research and Scholarship. “For public health reasons, we stopped work with in-person human subjects. We shut down most work in laboratories, in the field, and on boats. We worked very hard to put procedures in place so that some faculty could continue to do their research onsite — but not everyone.”

The Office of Research and Scholarship soon began crafting creative ways to allow students to finish their projects. Students who could complete their work remotely were given lab computers to analyze their data. Graduate students, at the apex of their studies, were allowed to finish their final experiments and defend their theses under strict physical distancing protocols.

In one special case, a student and now recent graduate took her lab home with her.

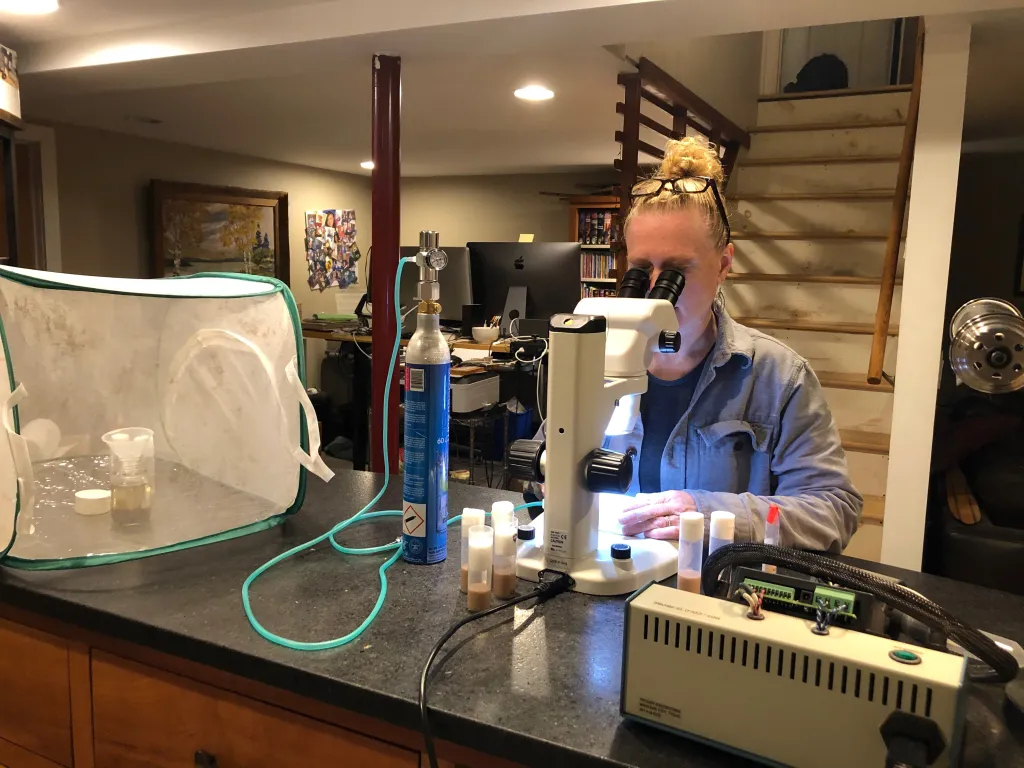

Julie Moulton, M.S. Biology ’21, was able to finish her master’s thesis on chronic pain from a makeshift laboratory set up in her home laundry room. Moulton’s research, out of the lab of Geoffrey Ganter, Ph.D., professor of biology, is helping to reveal targets for new drugs that may relieve chronic pain in humans.

The research was conducted by evaluating the pain pathways of fruit flies genetically designed for the experiment. In Moulton’s setup, a soda machine provided carbon dioxide to put flies to sleep for certain manipulations, and a desk lamp illuminated an arena for analyzing their behavior.

It wasn’t the sophisticated setting of the Ganter lab, with its rows of microscopes and complex instruments, but it made do. Moulton said the ability to finish her research at home was crucial in allowing her to graduate on time.

“It was very important to me to be able to continue working from home,” she said. “I was very close to finishing my thesis work and just needed to conduct one additional experiment. By working from home, I was able to complete my degree on time instead of pushing back my graduation.”

For Moulton, the burden of the pandemic soon brought benefits: she successfully defended her thesis in July and now works as a research associate for and manager of the Ganter Lab on UNE’s Biddeford Campus.

Experimenting with New Variables

It was not possible, however, for all students to build laboratories in their homes, but UNE, a university built on a culture of innovation, found ways to offer students virtual research opportunities in collaborative groups.

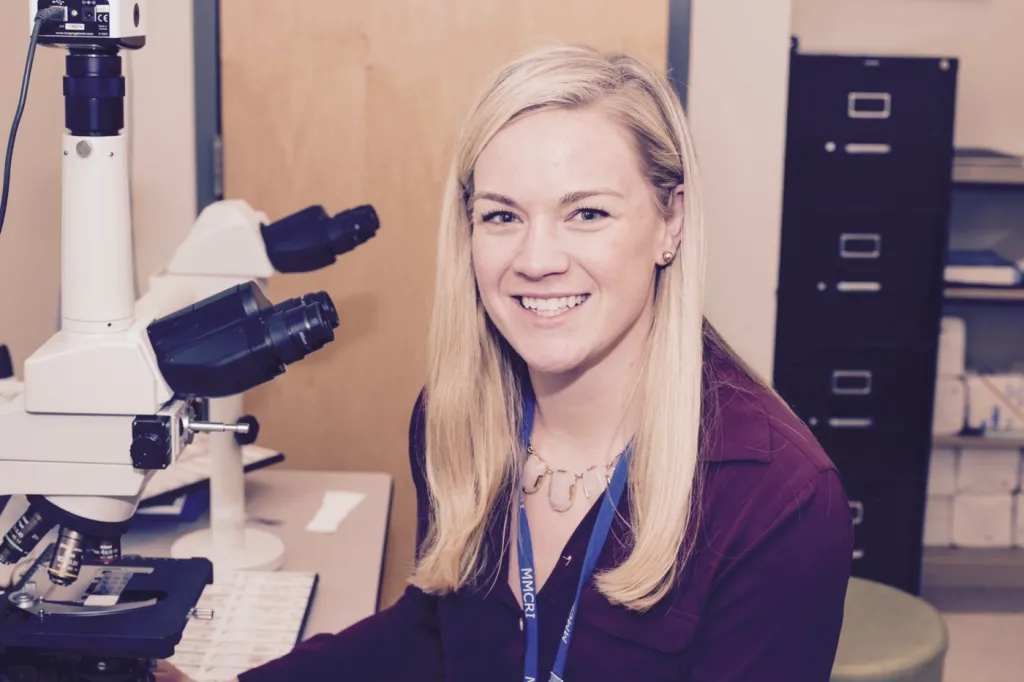

One such effort, dubbed the “Pathways Party” by Houseknecht, brought together three students — one from outside UNE — to analyze data that could help researchers understand the underlying protein mechanisms behind the unwanted side effects of antipsychotic medications on the heart and liver.

Working remotely, the students — Bisher Sultan (D.O. ’23), Radwa Ibrahim (D.O., ’23), and Elizabeth Bernier, a psychology student at the University of Southern Maine (USM) — regularly met with Houseknecht, as well as Meghan May, Ph.D., M.S., professor of microbiology and infectious disease, and Beau Rostama, Ph.D., a research associate, to review the data, which had come from animal experiments conducted the year prior.

Bernier joined the party after her research slot at Maine Medical Center — which postponed its student research opportunities because of the pandemic — was shut down. UNE gave her the avenue to pursue her studies when other options were exhausted.

“COVID-19 has absolutely complicated things, but being a part of research even remotely has really helped encourage me to stay on my career path,” she said. “It has meant a lot to me to have the opportunity to stay involved in things I genuinely care about. The Pathways Party is just one of the creative initiatives that UNE faculty developed on the fly to keep students engaged in original and meaningful scholarly work during this most unusual year.”

The reconfiguration of research is one of many ways the University stepped up to meet the pressing needs of today, Houseknecht said. During those first months of the pandemic, it became apparent that UNE was one of few schools in the region that could provide space for students and faculty to continue their important scientific work.

“All research institutions, world-wide, were facing the complexities of operating under pandemic conditions and we were charting new territory every single day,” the associate provost remarked. “I think one of the advantages of being a small university is we figured out how could we innovate in order to conduct some research.”

PERSISTENCE PAYS OFF

By the time it was announced in July that UNE intended to reopen in full for in-person learning in the fall, and every division within the University began to prepare for a safe return to campus, an intrepid, behind-the-scenes endeavor was already underway to reestablish research opportunities in as full a capacity as possible.

In nearly every discipline at the University, students very quickly began bringing their experiments to life.

Andy Robinson (M.S. Marine Sciences, ’21), who stayed in Maine throughout the spring and summer, carried out his research studying the currents in and around Biddeford Pool in hopes of identifying potential sources of pollution. Robinson worked with Michael Esty, B.S., technical and project specialist in the P.D. Merrill Makerspace, to fashion a set of drifters that use radio signals to relay their locations to Robinson’s computer. The pioneering radio communication system allows Robinson to track the drifters’ trajectory and the flow of water in and out of the Pool.

The project has the capacity to understand the cause of contamination that occasionally closes Biddeford Pool to local fishermen, a very real ecological and economic problem. Robinson said UNE’s capacity for research, plus its world-class facilities, have assured him he is on the right career path.

“UNE’s strong undergraduate research program has really reinforced my belief that I want a career in research in the marine field,” he detailed. “The research opportunities and experiences I’ve had at UNE have helped set me up to pursue a career in physical oceanography.”

From the vast expanses of the ocean to the tiniest of biological mechanisms, innovative research continues to emerge from UNE.

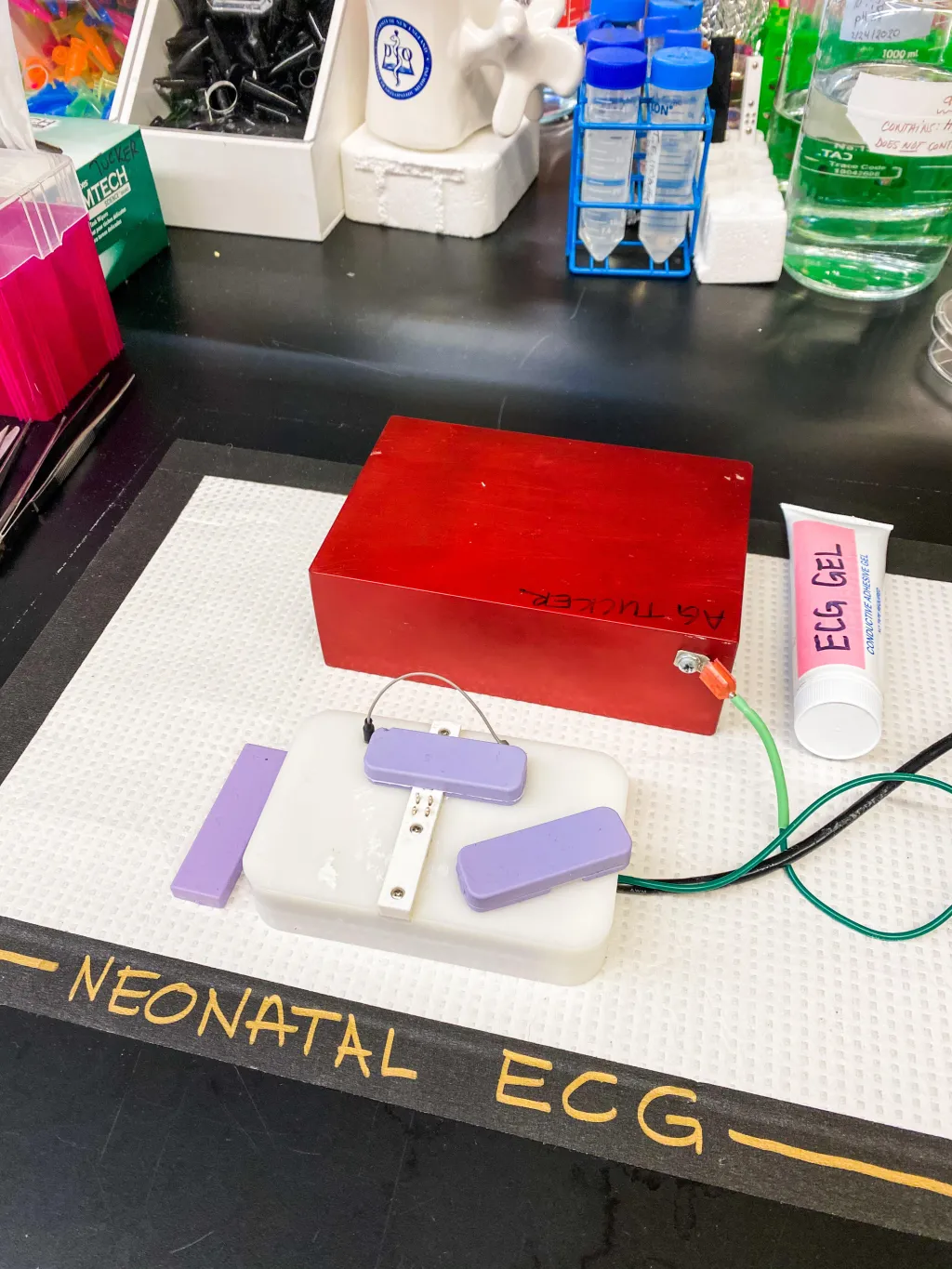

Just last month, researchers in the lab of Kerry L. Tucker, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Sciences, published a novel exploration into the assessment of neonatal, or newborn, mouse heart function using a noninvasive approach to monitoring the electrocardiography (ECG) of baby mice (pups).

The first-of-its-kind method is the brainchild of Lindsey Fitzsimons, M.S., RCEP/CES, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Maine Graduate School of Biomedical Science and Engineering who is completing her doctoral thesis at the Tucker Lab at UNE.

Fitzsimons told UNE News that the research is being used to better understand congenital heart defects (CDH), which are currently the most common birth defect, occurring in 1 in 100 live births in the U.S. each year. The researchers said their approach for assessing neonatal mouse heart function has the goal of better identifying, understanding, and treating the disease across species, including humans.

“The more parallels we can draw with rodent and human cardiac function, the greater the reproducibility and translatability of both basic science and clinical biomedical research,” she remarked.

Other success stories abound.

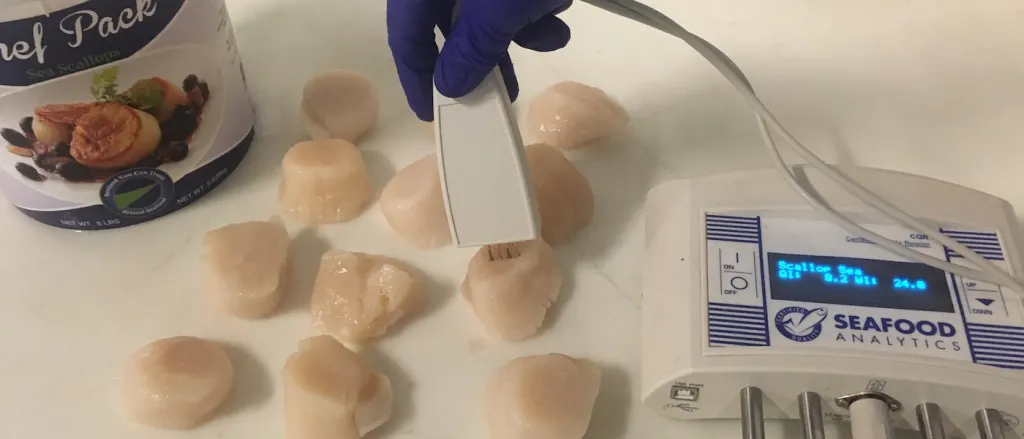

During the fall semester, UNE Professional Science Master’s student Joey Ehrhard worked with Bristol Seafood to validate a testing methodology to determine if scallops are fresh as opposed to frozen using a hand-held probe from Seafood Analytics that uploads data into a software program.

Kayla Looper (Neuroscience, ’21) returned to in-person work in the lab of Michael Burman, Ph.D., associate professor of psychology in the College of Arts and Sciences, in July, where she examined neuronal inhibition in an attempt to determine the role corticotropin releasing factor plays in the development of pain hypersensitivity following neonatal exposure to stress.

And an entire class at UNE, taught by Pam Morgan, Ph.D., professor in UNE’s Environmental Studies programs, spent the semester looking at ways of preserving the shorelines along the University’s coastal campus in Biddeford in an effort to mitigate erosion and save the shore’s marine ecosystems.

Triumph amid adversity

Even on an institutional level, enthusiasm around research has not slowed. In fact, Houseknecht informed, more UNE researchers submitted federal grants in the first quarter of the current fiscal year than they did at the same time last year, a testament to the UNE community’s commitment to improving the health of people and the planet through scientific discovery.

To date, over 40 faculty members have been approved, under contingency plans and enforced safety protocols, to resume research activity at the University. Restoring research at UNE was indeed a heavy lift, but with University-wide transmission of COVID-19 low and a community dedicated to creating a better tomorrow, Houseknecht said it was worth the work.

“It took a village, but I'm really proud of how our faculty, professional staff, and students have done,” she expressed. “We've had a lot of students, graduate and undergraduate, on campus doing research scholarship, and we’ve been able to host them here safely. I think that's a tremendous success.”