Maggie Stanton, Ph.D., uses her role as an instructor in one of America's few dedicated animal behavior programs to inspire the next generation of field scientists

All photos courtesy of Maggie Stanton

Both through her research on animal social interactions and passion for the profession, a faculty member in the University of New England’s Animal Behavior degree program is carrying out the legacy of the late Jane Goodall — and empowering her students to do the same.

Maggie Stanton, Ph.D., assistant professor of animal behavior in the School of Psychology and Brain Science, was recently invited to attend the memorial service for the storied late primatologist, ethologist, and conservationist who paved newfound pathways for women in field research studies.

While somber, and reflective, Stanton said, the service held at the Washington National Cathedral in November was a grand remembrance of the woman whose research on chimpanzee behavior inspired a new generation of scientists — like Stanton — to examine animal behavior from a naturalistic perspective and whose boundary-breaking pursuit of knowledge ushered in a new era of equitable research norms across genders.

“It was a very sad occasion, but it was really a celebration of life,” she said. “I felt honored to be invited, but also a responsibility to be present and pay attention: to listen to the stories, to understand the different parts of her life, and the unselfish life she led.”

Stanton, who has had the opportunity to meet Goodall in person, is an animal behaviorist who has studied the life cycles and social interactions of bottlenose dolphins in the waters off Western Australia. She currently studies the social behavior and development of chimpanzees in Gombe National Park in Tanzania, where Goodall’s pioneering work studying the behavior of wild chimpanzees first began over 60 years ago.

A young chimpanzee named Grendel (left), photographed by UNE Assistant Professor Maggie Stanton (right).

In her teachings within UNE’s animal behavior program — one of only about a dozen such interdisciplinary bachelor’s degree programs in the country — that work continues today.

From day one, Stanton’s student researchers use Goodall’s own data sets to study data trends in chimpanzee behaviors, contributing to a six-decade-plus body of work that continues to grow thanks to an interconnected network of scientific contributors across the globe.

“Students are literally working with the data that Jane started collecting,” Stanton said. “Her data are in that database, and these are the offspring and grand-offspring of the chimpanzees she watched in the 1960s.

“That connection is not lost on them,” she said.

Working with those long-running data sets, Stanton’s students are introduced early to the rigor and responsibility required of behavioral research. The records they analyze, gathered by Tanzanian field researchers in Gombe and dating back to the 1970s, document chimpanzee behavior minute by minute, offering a detailed record of maternal care, development, and social relationships across generations.

Once students learn how to interpret the data, Stanton said, they can trace how a chimpanzee family moves through a typical day, from time spent in nests and foraging to interactions with other members of the group.

The work is intentionally hands-on.

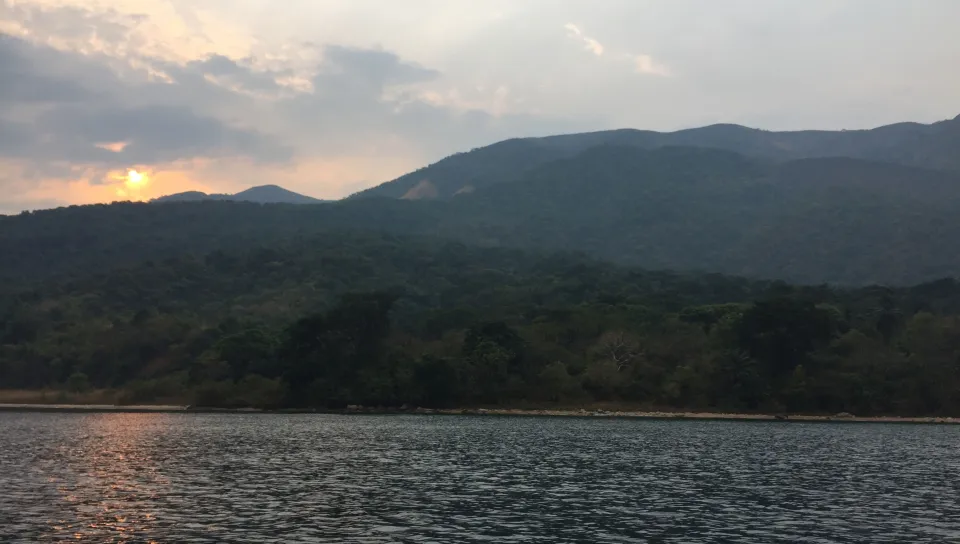

A family of chimpanzees — Gremlin, Grendel, Gaia, and Gabo (left) — in their habitat in Tanzania’s picturesque Gombe National Park (right).

Students begin by entering and organizing data before progressing to more advanced analysis, learning how research questions are developed and how evidence is managed within a long-term scientific study. The experience reinforces research methods taught early in the animal behavior curriculum and helps students connect course concepts to applied research.

“These are the same techniques we teach in our introductory methods courses,” Stanton said, “so students are seeing a direct application of what they learn in class, working with real data that are still being collected today.”

That emphasis on method, she noted, allows students to transfer their skills across systems and species.

“One of the reasons I love methods is because you can use them to study any species,” she said. “Once students understand how data are collected and analyzed, they can take that experience anywhere.”

Many students enter UNE’s animal behavior major with an interest in animals; others discover the field through coursework that blends biology, psychology, ecology, and quantitative analysis.

Bottlenose dolphins, the subject of Stanton’s research in Western Australia’s Shark Bay, a World Heritage Site in the country’s Gascoyne region.

As a bachelor of science program housed within the School of Psychology and Brain Science, the program allows students to explore both cognitive and biological approaches to behavior while developing analytical skills expected in professional settings.

For students preparing for veterinary school, Stanton noted, participation in recognized research initiatives provides meaningful preparation.

“I’ve had a number of students who were pre-vet and went on to veterinary school,” Stanton said. “This counts as research experience, and it’s something they can point to directly in their applications.”

“People didn’t always think animals could have personalities, or that it was acceptable to name your subjects,” she said. “Those ideas didn’t just appear — they were argued for, and that history matters.”

Stanton noted that, as students advance within the program, they have the opportunity to undertake independent research initiatives, and many go on utilize their training in diverse contexts.

Whether pursuing research, veterinary medicine, or related fields, students graduate with experience working in a discipline shaped by decades of careful observation, data collection, and field-based inquiry.

“Working with these data helps students understand what it really means to do behavioral research,” Stanton remarked. “They see how questions are built, how evidence is handled, and how long-term studies shape what we know.

“That experience stays with them,” she said.

The sweeping landscapes of Gombe (left) provide ample space for chimpanzees, like Ferdinand (right), to flutter from branch to branch.

Jennifer Stiegler-Balfour, Ph.D., interim director of the School of Psychology and Brain Science and professor of psychology, said Stanton’s work reflects the strengths of UNE’s animal behavior program and the University’s emphasis on undergraduate research.

At UNE, 46% of undergraduates participate in hands-on research, more than twice the national average.

“We are truly fortunate to offer a strong and unique program as Animal Behavior here at UNE,” she said. “Providing undergraduate students with the opportunities to work closely with our exceptional faculty as they explore and shape their career paths in an incredible asset to the University."

Stanton said her teaching is informed by an understanding of how the field of animal behavior developed, as well as how much of what is now standard practice was once contested.

“It’s not lost on me that we wouldn’t have animal behavior, at least not in the way it exists now, without Jane Goodall,” Stanton said. “She wasn’t the only one who shaped the field, but she helped change how the field thought about animals — and who was allowed to do that work.

“A major like this, a program like this, probably wouldn’t exist without her,” she said.