An Oral History of the Coming Transformation of UNE’s Portland Campus

On October 6, 2020, UNE received a gift of $30 million from the Harold Alfond Foundation to support construction of a new facility for the relocation of UNE’s College of Osteopathic Medicine (COM) from the Biddeford Campus to the Portland Campus, the establishment of a new Institute for Interprofessional Education and Practice (IIPEP), and the acceleration of high-growth programs on the Biddeford Campus.

Once the new facility is established in Portland, that campus will become something unique in New England and rare in American higher ed: a concentrated hub dedicated to educating students in multiple health professions programs. This is a watershed moment for UNE, nothing less than the next leap forward in the evolution of a university that has always had the moxie to dream big, and the result will have profound impacts on our student experience, Maine’s critical workforce needs, and the improvement of health outcomes for people across the state and the region.

But turning a dream on this scale into reality takes the sustained, concerted effort of hundreds of people: collaborating with the Alfond Foundation and other generous donors, planning the construction process, optimizing academic programming, assessing cutting-edge technology — and doing it all amid the unprecedented challenges of the ongoing COVID pandemic.

We spoke to seven people at UNE who are deeply involved in this ongoing effort and asked them to tell us the story in their own words.

Introduction

JANE CARREIRO, D.O., Dean of the UNE College of Osteopathic Medicine: Moving the College of Osteopathic Medicine [COM] to the Portland Campus is going to be transformational. It’s like COM

is growing up in some ways, you know? We’re leaving our childhood home, and we’re moving.

JAMES HERBERT, Ph.D., President of UNE: What I’m really excited about is establishing the Portland Campus as our health sciences campus in the public mind.

As long as COM remains down in Biddeford, if I were to call Portland our “health sciences campus,” it doesn’t quite add up. So, we’re finally going to be able to brand that very clearly. This is our health sciences campus. And guess what — we will have a higher concentration of diverse health care programs on a single footprint than any place else in New England. This is going to cement, once and for all, our reputation as the provider of Maine’s health care workforce.

KAREN PARDUE, Ph.D., RN, Provost of UNE (former Dean of UNE’s Westbrook College of Health Professions): The fabric and the culture of the Portland Campus is interprofessional education, and we’re doing it really well.

But the feedback we get from faculty, professional staff, and students is, “Where are the medical students?” because the health care team always has a physician there. So, I’m always cautioning people to say, yes, this new building is the home for the College of Osteopathic Medicine; and they absolutely need a home. That’s part of the identity of the college. But that doesn’t mean the only people in there will be COM students. If we do that, we’ve missed an opportunity because we might as well just build a box somewhere — that won’t achieve what we’re looking for.

This is going to cement, once and for all, our reputation as the provider of Maine’s health care workforce. — James Herbert

Background

AL THIBEAULT, Vice President for University Operations: After the UNE merger with Westbrook College in 1996, that’s when the idea of moving COM to Portland first started to bubble up, but it wasn’t heavily discussed. Then in 2001, Nursing, Social Work, and Physical Therapy went to Portland, and we had that first thrust of combining the health professions on one campus, so it came up again under [former UNE President] Dr. [Sandra] Featherman. But it didn’t have the traction because of the heritage. Historically, COM has always been a cornerstone of the Biddeford Campus.

A lot of people, including some of the COM alumni, faculty, and current students felt it should stay there.

JANE: For many years there’s been a big resistance about moving COM. And I was the first one. In my first meeting with James, I said, “Absolutely not.” I said, “If I don’t get to the point where I think this is

the best thing for COM, I’ll find a reason to resign so you can do this without me.”

ELLEN RIDLEY, Assistant Vice President of Advancement Strategy: When President Herbert came on board,

one of the first questions that he asked, I think even during his interview, was, “How come the medical school is not in Portland?”

AL: President Herbert came in, did his year of walkabouts and talkabouts and discussions with people on needs and priorities, and the idea of moving COM to Portland bubbled to the surface for him. He saw that, now, the time was right. You know, “We need to elevate what we do best.”

JANE: What started to change my mind was, developmentally, it’s very difficult for medical students, who on Tuesday morning are going into a hospice to take care of somebody that’s dying, and on Monday and Wednesday, they’re on the Biddeford Campus with undergraduates; they’re surrounded by people who are in a different developmental stage, people who are just figuring out what they want to do. There’s such a developmental schism. That really moved me, and I started to see the possibilities.

JANE: I went up and spent time on the Portland Campus. It has a different atmosphere because the students are all older developmentally, and that is the message that I’ve been sharing with everybody. We’ve had regular meetings with alumni, and I show them the building plans. I tell them, “I don’t want this move to end up being ‘they’ moved,” right? “I want it to be ‘we’ moved.” I think that’s really important, to bring the alumni into the conversation. And I think people are really seeing it and saying, “Yeah, this makes sense!”

Working with the Harold Alfond Foundation

ELLEN: You do something called creating a case. What is the case for moving COM to Portland? What is the case for creating the Institute for Interprofessional Education and Practice? Why is it needed? What will it do for Maine? How much will it cost? And the donor then gives you the green light and says, “That sounds like something that we might be able to get behind.” And, of course, it’s always based on the donor’s priorities. In this case, the project was a really excellent fit for the Alfond Foundation’s priorities and their mission.

JAMES: Greg Powell, the head of the Harold Alfond Foundation, has been a phenomenal partner. I meet with Greg regularly, and he’s continued to help us think through the various implications of this project and how it will impact the state as a whole. We couldn’t ask for a better partner than him.

ELLEN: We started substantive work on the draft proposal in June of 2019, and then James met with Greg Powell at the Cumberland Club in July. A couple of weeks later, we submitted a highlights document that was prepared by the Institutional Advancement team, led by [Vice President for Institutional Advancement] Bill Chance and James. After that, Greg and Travis [Cummings] from the Alfond Foundation came to the Biddeford Campus for a tour. At that point, we began to realize that not only was the foundation interested in the move of the medical school, but they were also really interested in finding out what would happen to the spaces that were vacated on the Biddeford Campus. Moving COM would open up significant classroom space, and space is a challenge there. The project became bigger and more comprehensive at that point.

We’re all so grateful to the Alfond Foundation for the opportunity to create something special.

— Karen Pardue

ELLEN: My biggest recollection is working through Christmas [2019]. It was a 24/7 type of endeavor, with lots of thinking about the details and what’s going to make the best case. The grant writer’s job is to cull and edit and fine-tune material from many different sources. The response document was really the most collaborative moment in our work together because that involved Nicole Trufant, Bill Chance, [Associate Provost for Academic Affairs] Mike Sheldon, Karen Pardue, Shelley Cohen Konrad, Jane Carreiro, and, of course, James himself. It was a very heavy lift. I spent all of Christmas vacation in my office. James ended up sending me a box of chocolates!

KAREN: We’re all so grateful to the Alfond Foundation for the opportunity to create something special. Because this isn’t just putting up a building. We’re creating an educational experience that can’t be replicated anywhere else.

ELLEN: In my writing, I like to focus on the emotional connection. So, writing about Harold Alfond, it’s very meaningful to me to think about this man who loved Maine, who obviously worked really hard, and had the good fortune to have this huge financial legacy to leave to the state. That’s such a celebratory thing to talk about. I love that part of this work.

Making it Happen

NICOLE TRUFANT, CPA, Senior Vice President of Finance and Administration: It’s so freaking complicated! Because you have to build the facilities building, you have to move the National Guard out…You know that, right? Ask Al what he has to do to get this thing done.

AL: In order to move COM to Portland, we’ve got to build the new COM building behind Innovation Hall. But behind Innovation Hall resides the National Guard and their vehicle maintenance facility. Allowing that to remain was a condition of the transfer of the armory.

[The old National Guard Armory building was acquired by UNE in a 2015 land-swap agreement and converted into UNE’s Innovation Hall, which opened in 2017.]

AL: But in order to build the new COM building, we’ve got to get them out. Well, they’re not ready to go until…well, before COVID, it was ’23. Now it’s probably ’24, ’25. We had basically three options. So, first I said, “Look, I need you to leave so that we can build a building. You’re in the way.” They laughed at me. They said, “We’ve got no place to go.” My second option is I can rent and renovate a building to accommodate them somewhere. Or, option number three: we can build a building on campus that meets our future needs, put the National Guard there for a couple of years, and then when we move them out, finish that building so it can become the new facilities management building for UNE. So, we’re not throwing away money. That was our best alternative.

AL: I had a long conversation with the lieutenant colonel. When he stopped laughing, after I told him this is what I wanted to do, he said, “What makes you think we want to move twice?” And I said, “Well, because I’m asking nicely.” We had a very good relationship with their senior staff, including the general, with whom I had worked when we did the armory transfer. He and I did all the presentations to the different planning boards. We had worked together quite a bit. And he said, “Tell me what I gotta do, and I’ll help you.” And so the lieutenant colonel told his people, “Work with UNE, and tell them what you need. Not what you want — what you need, so we can do the bare bones.” And they’ve agreed to move into our new facility until their new facility is available.

KAREN: It’s also a really challenging time to be building. Materials are crazy. I mean, they say steel will take nine months to get here — if we can get it.

AL: The thing that’s changed the most is COVID’s impact on the economy. It’s like a huge set of handcuffs. We used to be able to get steel in about six, eight weeks. So we built our schedule to accommodate the traditional construction schedule. Now, we talk to people about steel: it’s twice the price. And you’re not getting it in six weeks. You’re getting it in seven months.

ELLEN: The fact that COVID happened meant that the Alfond Foundation ended up having

all kinds of additional questions about how we were going to do this given the impacts of the pandemic. So that was another three or four months of providing documents.

NICOLE: I was very much involved in assuring the foundation that our financial health was strong, that we were going to be able to weather this storm and come out of COVID. And it was also important to show that we would be able to build without impacting our student experience, that we would still be relevant in the marketplace.

NICOLE: I also set up a committee, a COM building leadership group that I am co-chairing with the provost. We meet weekly to go through plans and to make final decisions, in consultation with the president, with respect to the building.

KAREN: I enjoy bringing together various groups of people: Jane and [Interim Dean] Sally [McCormack Tutt], who is now representing the Westbrook College of Health Professions, and Al Thibeault and [Director for Campus Planning] Eric Mora who are essential because I know very little about building design itself. I know a lot about pedagogical design and active learning spaces. So, the opportunity to kind of marry all these talents to envision what this can be is wildly exciting.

NICOLE: Alan and I have meetings with board of trustees members to keep them involved in the process, which is helpful because they have such great expertise. One is an engineer and another one is a commercial real estate developer. And I have four national boards that I serve on, with my colleagues, two of whom built medical schools recently. I’ve been reaching out to them, getting ideas and best practices.

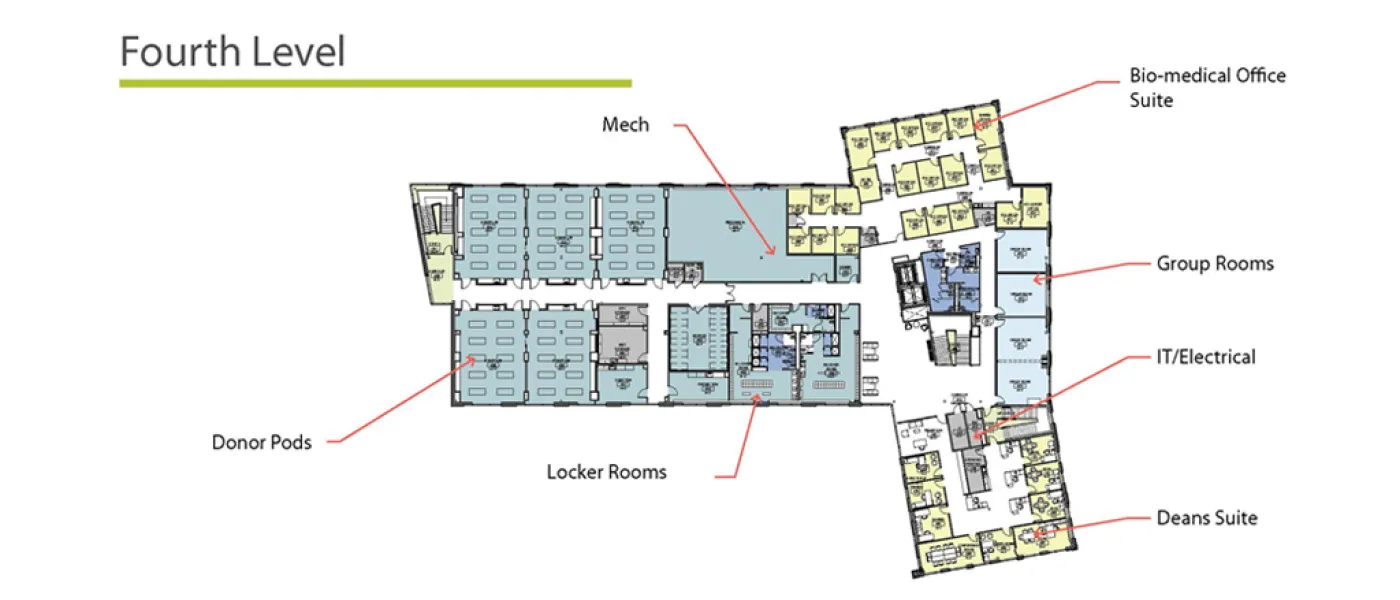

JANE: Back in August [2020], I set up work groups at COM, divided by department. I posed the question, what do we want to be in five years? In 10 years? And I just let them have at it. Then we brought all the information together, and there was a list of about 12 commonalities that everybody hit on: We all want to be together. We want to have a face that says, “This is COM.” We want to feel welcoming. We want to see the natural world. We want it to feel like home. It was great because there was so much consistency, so it was easy to bring that to the design team.

NICOLE: I’m working closely with Alan and Eric on the design of the building from the budget perspective. Because we can’t just look at the cost of building the building. What’s it going to cost to operate that building longterm? Because that becomes part of the budget cycle in perpetuity. So those are really important decisions.

JANE: For the most part, that first design that the architects came out with captured all of those commonalities that everybody had. We all looked at it and said, “Wow, that’s exactly what we were thinking!”

The New Building

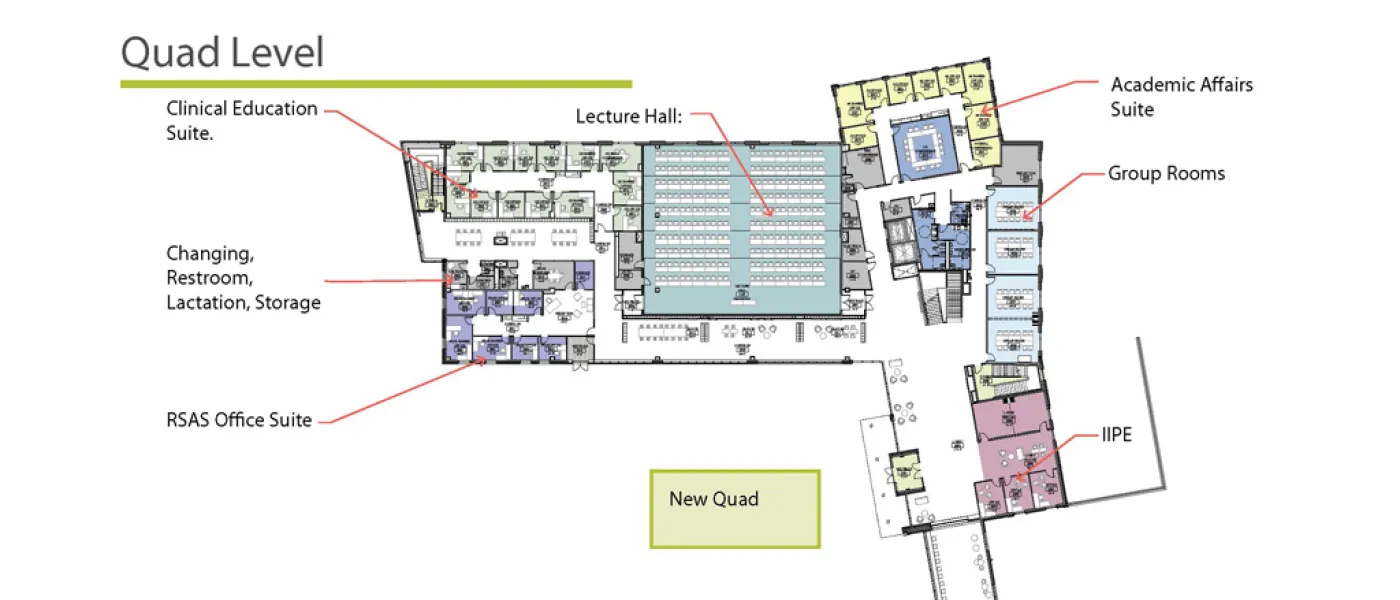

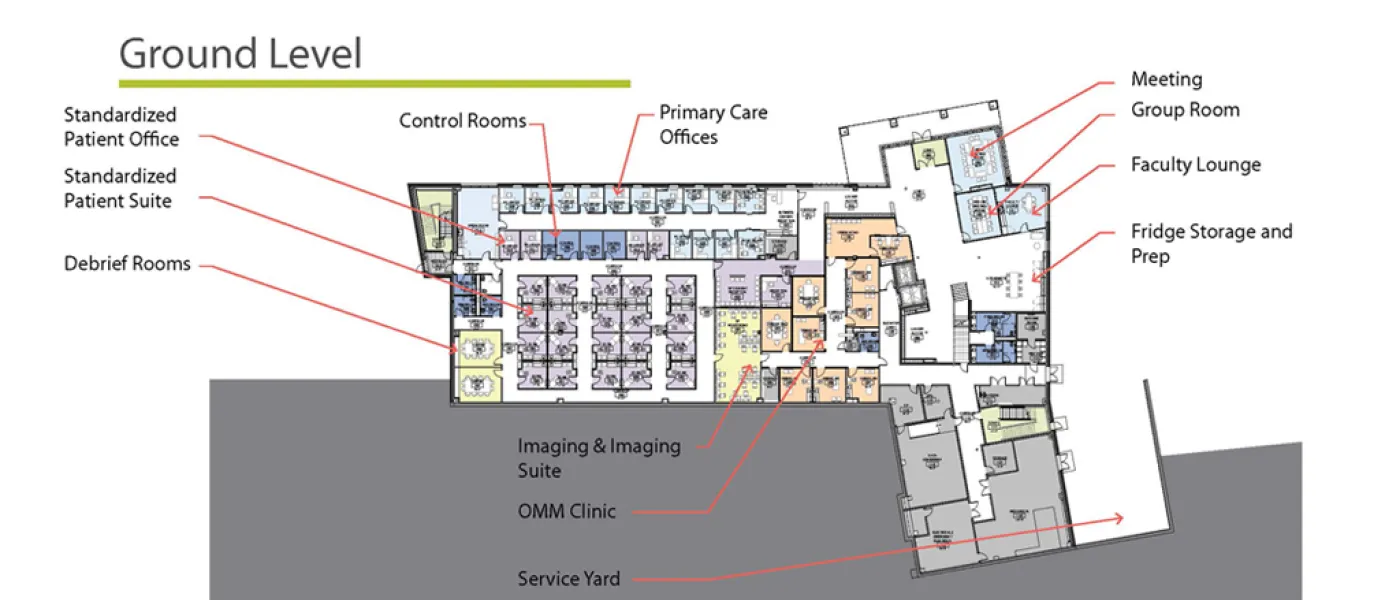

KAREN: The new building is being designed with a lot of intentionality to mix and mingle and braid different groups of students together in a very organic way.

AL: One of the things that we’ve been very, very conscious of is the need to integrate COM into the fabric of the Portland Campus. So the location of the building, the physical connection of the building to Innovation Hall, will allow for that synergy and the cross-pollination.

KAREN: It made no sense to create a simulation center in the new building because we already have one. We need to expand its footprint, but we don’t need to recreate what we already have. So, a large walkway is being created to connect Innovation Hall to the new COM building, and the COM students will be coming over to Innovation for their simulation experience, just as health professions students do. And that will make it so much easier for faculty to design true team-based simulations.

AL: But the other side of that coin is that we still need to give COM an identity. We’re working very hard to give them a home, a place that they can truly call their own and say, “This is the College of Osteopathic Medicine.” So, when they’re recruiting students, they can showcase their building, their facilities, their home, but it’s still woven into the fabric of the campus. And by “woven in,” I don’t mean just physically tying it together but in terms of culture and programming.

KAREN: One thing that’s really being emphasized as we design this building is pedagogical effectiveness and design for interprofessional education and practice. The classrooms will be active learning spaces with a lot of flexibility so that they can accommodate, say, a typical lecture or presentation of content but also provide the opportunity for small breakout groups where students can apply that content to a case or a situation.

The location of the building, the physical connection of the building to Innovation Hall, will allow for that synergy and the cross-pollination.

— Al Thibeault

KAREN: We’re also working very hard, with [Director of UNE’s P.D. Merrill Makerspace] Justine Bassett’s leadership, to be sure that health professions students are exposed to the concepts of design thinking and problem solving. Like most professions, sometimes we just do things because that’s how we’ve always done them. And nobody’s really thought about, “Okay, what’s that about?”

JANE: A health professions-dedicated makerspace will be a huge opportunity for health professions students to get together and work on projects and come up with great ideas. To be working with, say, occupational therapists or dental students, you get a whole new perspective on what might be possible to help a patient.

KAREN: The pandemic has taught us a lot about telehealth. Right now, in Innovation Hall, we have virtual reality simulation in one of the suites. And it seems to me that some version of telehealth also belongs there because I do believe that our students need that basic competency. And I don’t mean on the equipment. It’s not just about knowing which button to push but having a mental model of how telehealth works and how to build a relationship or conduct an interview over this video channel.

The Importance of Interprofessional Education (IPE)

SHELLEY COHEN KONRAD, Ph.D., LCSW, Director of UNE’s Center for Excellence in Collaborative Education: The move of COM to Portland cements the culture of interprofessional learning. The Center for Excellence in Collaborative Education [CECE] has been around at UNE in one form or another now for 11 years doing this work. Creating a health sciences campus with our medical college on it is a really validating statement. It says that UNE is truly, deeply committed to interprofessionality — committed to a pedagogy that is cross-professional, cross-disciplinary, experiential, and interactive.

KAREN: We know from years of doing interprofessional education that it isn’t just putting students in a room to learn together. They need that co-location opportunity to have lunch together, study together, ride the shuttle back and forth from the parking lot. It’s those casual and informal relationships that really blossom into a true team-based, collaborative practice approach.

SHELLEY: The national and international landscape of what we mean by “interprofessional” is changing. In 2016, the national IPEC [Interprofessional Education Collaborative] association changed a lot about the health competencies they were looking for. I think the most important part of that was recognizing that in order to really focus on health, you need to look beyond just health care and look at the environment and issues of poverty and social determinants. And to do that, it wasn’t just health care providers that needed to be trained as team members but people in the humanities as well.

UNE is truly, deeply committed to interprofessionality — committed to a pedagogy that is cross-professional, cross- disciplinary, experiential, and interactive. — Shelley Cohen Konrad

KAREN: Health professions education has been so siloed for so long. I’m a nurse by background. I didn’t know who anybody was or what anybody did when I graduated. We didn’t even talk about that. There are clinicians out there practicing now who really don’t know anything about IPE. So, in addition to teaching our students, we’re also offering opportunities to up-skill or inform the practicing world around interprofessional education and practice.

SHELLEY: We’ve done all along quite a bit of workforce development. Not only in Maine, but around the country, we’ve been invited to do various kinds of trainings in various kinds of clinical programs. But it’s much harder, as I like to say, to “train backwards” — to have people thinking outside of how they were taught originally when they were at university, when they were doing their clinical education. So, we’ve tried to develop innovative models where we customize the kind of training that we provide.

We’ve tried to develop innovative models where we customize the kind of training that we provide.

— Shelley Cohen Konrad

KAREN: CECE is the hub for IPE at UNE, but while Shelley knows most of the projects that are going on, IPE has become so much a part of the fabric of how the faculty thinks, at least in Portland, that there’s always lots of little projects going on that she doesn’t even know about — and they certainly don’t need CECE’s blessing, but she has sort of been the hub of this with all these spokes going everywhere. That, to me, is the exciting part. That tells us that IPE at UNE has been really successful because we don’t need one leader organizing this; it just happens spontaneously.

SHELLEY: I mean, when I hear what’s going on in other universities, I feel like we’re doing really well, you know, in terms of support, cultural adoption, visibility, the variety of programming that we have, that we’re inclusive in the way that we are inclusive…Yeah, we’re doing really well.

That tells us that IPE at UNE has been really successful because we don’t need one leader organizing this; it just happens spontaneously.

— Karen Pardue

Conclusion

JAMES: Everybody is all in. People get it, they understand it, and they’re excited about it. I think the vision is very compelling, and it’s compelling to people in a lot of different stakeholder groups, from faculty to administrative leaders, to trustees, our partners in business, government…The people in the community whom I talk to are very excited about it. Our partners in the big medical systems are very excited about it and have written us incredibly enthusiastic letters of support for the state and federal funding we are pursuing.

ELLEN: From an Institutional Advancement perspective, when we have a big, exciting, transformative project, it’s a moment in time to engage people and really grow the profile of the University. When I first came to UNE, we were just beginning the conversation about opening a dental school. The entire state of Maine understood that this was something that was really critical. This is another one of those projects. We’re going to be able to look back on this 10 years from now and say, “Wow, look how that changed Maine, and how it changed the University of New England, how it improved our relationships with our clinical partners, how it advanced interprofessional education…”

AL: I started here when it was embarrassing to tell people where you worked. Nobody knew where it was. Nobody knew what we did. And quite frankly, when you came to campus, it was embarrassing. You’d have guests to the campuses, and things were run down. They were too small for what we were trying to do. The facilities weren’t nearly as good as they are now.

NICOLE: I can’t describe to you the pressure and the burden of logging into the bank three and four times a day to make sure you’re going to be able to make payroll. You never forget that feeling, ever. Ever. And I swore, as long as I sit in that chair, that we would never be in that position again. I never imagined that we’d be in the place that we’re at today. So we don’t take it for granted. We remain, at heart, a little school with the big dreams.

AL: UNE is looked on in a completely different light now. I look back, and, to me, it’s like, “Oh my God, look what we’ve done!” When I started at UNE, our facilities totaled 400,000 square feet. Now we’re at 1.6 million. I’ve overseen construction for more than half of our square footage, on all three campuses. When you look at what UNE has done in the last 20 years, it’s mind-blowing.

KAREN: It will be a dramatically different professional campus than anything I’m aware of across the country. I can’t think of an organization that, in our footprint, has a medical school, a dental school, nursing, pharmacy, the therapies [occupational and physical], physician assistant, anesthesia, social work... I mean, this is incredible. And while this is terrific for COM, it’s also terrific for all those disciplines too. It’s another distinct value proposition as to why a student would choose, say, nursing or PT at UNE. It benefits everyone.

JAMES: Everyone in the health professions is keenly aware of disparities in health care, whether due to income, race, gender identity, location... It’s something we talk about constantly at UNE: how to address those disparities and close those gaps, especially in a predominantly rural state like Maine. So really, the most important thing, by far, is why we are doing all this now. The new facility will allow us to increase the class size of our med school and other programs, to train more doctors, and to improve outcomes through team-based care. Expansion of IPE and other programmatic aspects will allow us to increase our focus on diversity and cross-cultural competencies; and tools like telehealth will allow providers to reach even the most isolated patients. So, this is vitally important to the health of Mainers and people across the region.

SHELLEY: My hope is that, several years after COM comes here, IPE is just what they do. So we don’t even have to say, “Hey, we do

interprofessional education!” right? My hope is that we will have common classes where students from different programs come together to learn, and that’s just how UNE makes its mark — that’s just how we do business, and it’s not a big deal. That’s what I would love.

JAMES: UNE has been this place that has periodically reinvented itself. First there was St. Francis College and the New England College of Osteopathic Medicine, and they merged to become UNE. And then you had the merger with Westbrook College. I think this is another one of those watershed moments in UNE’s evolution. Every day we’re working on smaller things, you know, launching a new program here and a new initiative there, which are great, but you also need periodically to step back and dream big — do something bold and transformational for UNE. And really, more importantly, transformational for the impact that we have on the state and the region.

JANE: What the new building is going to give us is, all those places where we’ve been cutting corners and trying to do workarounds, we’re not going to have to do that anymore. And the faculty, staff, and the students are just ecstatic about that. There will finally be enough space to do all the things we want to do. I think that that’s the biggest thing, that it’s going to give us a springboard to move into the future. The other big thing is that we’re all going to be in one building, instead of spread out across campus. That feels really good to everybody. When I talk to my colleagues, they’re all excited. They’re like, “Wow, you’re getting a new building! You’re moving to Portland!”

Bonus Content: Photo Gallery