Assessing Curricular and Co-Curricular Student Learning

Guided by the understanding that outcome-based student learning assessment provides the tools to communicate about, understand, and advance student learning in curricular and co-curricular areas, UNE’s University Assessment Committee (UAC) has put together the following mix of assessment resources.

The materials reflect the UAC’s mission of enhancing, facilitating, and making transparent a university-wide student learning assessment system, and its vision of expanding, promoting, and facilitating equity-based and equity-driven assessment practices, to advance student learning in UNE’s curricular and co-curricular areas.

Key Steps of An Assessment Process

Assessing curricular and co-curricular programs’ educational effectiveness entails several key steps. Once curricular and co-curricular programs establish their learning outcomes and measures, they then identify each outcome’s benchmarks or target goals, collect and analyze the data, and make decisions based on the findings.

Wiggins and McTighe’s (1998) backward design serves as a model for making student learning central. Unlike the traditional, frontloading framework that involves designing curricular and co-curricular offerings around the content and materials, backward design begins by establishing the student learning outcomes, determining the assessment measures, and then planning the learning materials and instruction around those outcomes.

Following the contributions of Montenegro (2020), and Lundquist and Heiser (2020), this assessment wheel adds another essential component to the steps — students and other stakeholders. To create an inclusive assessment process, Montenegro and Lundquist and Heiser, recommend involving students and stakeholders at every step by including their voices and input and considering their positionality, intentionality, and power. They advise us to keep the human at the center of assessment design and practice.

Sources

Lundquist, A. E., & Heiser, C. A. (2020, August 21). Practicing equity-centered assessment. Campus Labs. https://www.anthology.com/blog/practicing-equity-centered-assessment

Montenegro, E. (2020). Focus on students and equity in assessment to improve learning. In N. A. Jankowski, G. R. Baker, K. Brown-Tess, & E. Montenegro (Eds.), Student-focused learning and assessment: Involving students in the learning process in higher education (pp. 187-209). Peter Lang.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (2nd ed.). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Applying Analytical Frameworks to Assessment

Analytical teaching frameworks provide the tools to create welcoming, inclusive, and meaningful learning environments and assess student learning.

UNE’s University Faculty Assembly Academic Affairs Committee’s Teaching Effectiveness Framework (TEF) makes student learning outcomes and assessment essential components to teaching effectiveness.

UNE’s Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning (CETL) has also developed resources to support inclusive learning environments.

- CAST’s Universal Design for Learning

- Mary-Ann Winkelmes’s Transparency in Learning and Teaching

- Indigenous research methods, pedagogies, and wisdom traditions

- Sources

- Chilisa, B. (2019). Indigenous research methodologies (2nd ed.) SAGE Publications.

- Shotton, H. J., Lowe, S. C., & Waterman, S. J. (Eds.). (2013). Beyond the asterisk: Understanding Native students in higher education. Stylus.

- Walter, M., & Andersen, C. (2013). Indigenous statistics: A quantitative research methodology. Routledge.

- Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Fernwood Publishing.

- Sources

Designing Student Learning Outcomes

Student learning outcomes provide the central mechanisms to assess and ensure curricular and co-curricular student learning. They serve as the foundation for curricular and co-curricular programs to develop their curriculum, select their instructional methods and materials, and create their assessment measures. They also promise that students who successfully complete the program will achieve those results.

Cognitive, Affective, and Psychomotor Domains

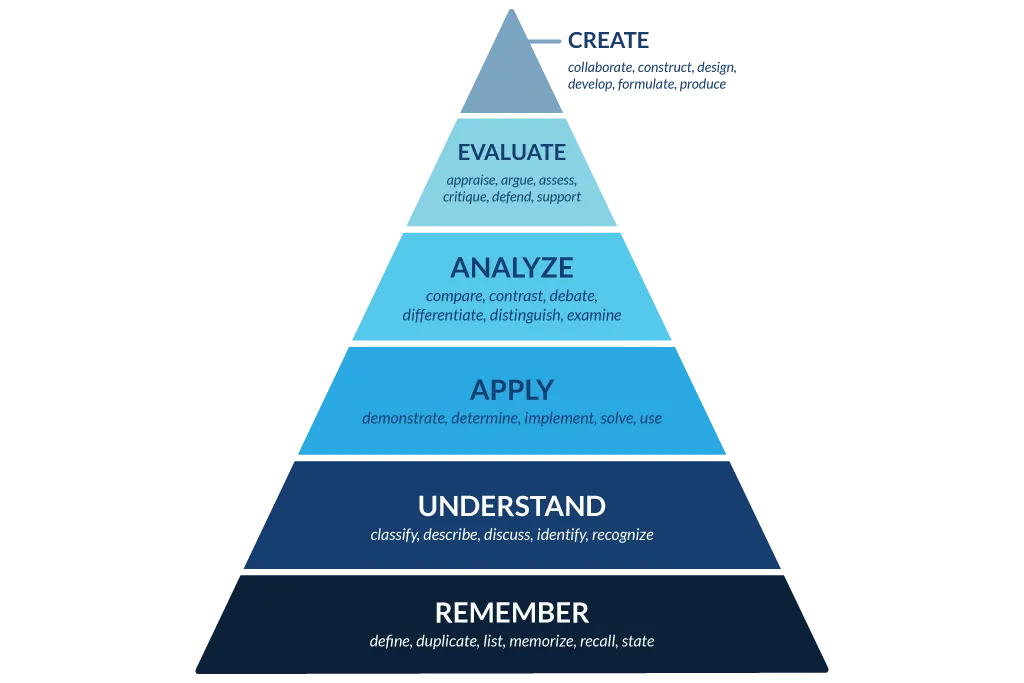

To write student learning outcomes, assessment practitioners have typically turned to the cognitive, affective, and psychomotor learning domains that educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom and his colleagues first articulated (1956). Later, Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) revised the original Bloom’s cognitive taxonomy by modifying the hierarchical order of cognitive development, and changing each category name from a noun to a verb.

Bloom and his colleagues also designed the affective domain to measure attitudes, emotions, and values, and the psychomotor domain to measure kinesthetic or physical skills.

View the affective and psychomotor domains quick guide (PDF)

Bloom’s and Beyond

Since Bloom’s publication, other scholars have offered their own frameworks that classify and measure learning in various fields, environments, and domains.

Aligning Learning Outcomes to Learning Experiences

Curriculum maps are essential tools to ensure curricular and co-curricular programs align student learning outcomes with curriculum, and teach and assess all student learning outcomes in a sequential, scaffolded order.

Curriculum maps also serve many other purposes. They help new programs in development plan the curriculum and existing programs revise, reinforce, and assess their curriculum. They ensure a program’s structural integrity and intentionality. They also convey the program’s learning expectations and the curriculum’s progression to students and stakeholders .

View the achieving curricular alignment using curriculum maps quick guide (PDF)

Selecting and Designing Measures

Assessment measures provide the tools to not only assess student learning, but also gather quantitative and qualitative data that, when directly aligned with the learning outcomes, demonstrate the degree to which students have achieved those outcomes.

Carefully selecting and designing well-aligned, well-written measures at the achievable curricular or co-curricular level gives students the surest opportunity to demonstrate their learning, and results in more reliable data. Using a combination of formative and summative, and direct and indirect measures also offers students varied ways to demonstrate their learning, and allows faculty and professional staff to triangulate the data and attain a comprehensive picture of student achievement of each learning outcome.

View the selecting and designing assessment measures quick guide (PDF)

Using Rubrics

Among the steps in the assessment cycle, rubrics stand out as beneficial for communicating curricular and co-curricular expectations, assessing learning, and collecting consistent data.

- They make transparent the criteria students are expected to meet on an assessment

- Provide clear feedback to students on their strengths and areas for improvement

- Serve as guides for faculty and professional staff in refining teaching methods

- Serve as guides for peer reviewers in providing their fellow students with feedback

- Help faculty and professional staff uniformly assess student learning

- Result in the collection of a more reliable data set on student learning

While rubrics take shape in various formats, analytic rubrics get recognition for communicating performance levels and their rating scale especially on measures such as written work, presentations, and group projects. Analytic rubrics list the key elements or attributes typically on the left-hand column of a grid that faculty and professional staff will objectively assess within students’ work. On the top row, analytic rubrics denote the performance levels (e.g., exceeds standard, meets standard, approaching standard, needs support) and their numerical scale. Then within the grid’s spaces, analytic rubrics provide brief, objective descriptions that differentiate one performance level from another.

Setting Benchmarks or Target Goals

Standard assessment practices include ascribing a benchmark (also known as a target goal, standard, or threshold) to each student learning outcome. Benchmarks help academic programs and co-curricular units determine their expected or desired level of student learning success, communicate the degree to which they have met their learning outcomes, and set aspirational goals to achieve in the future.

Reporting on Student Learning

Reporting student learning outcomes data and findings necessitates insight, intentionality, and a vision. Assessment practitioners use the data to tell a story about their curricular or co-curricular program, capture the attention of their audiences, and promote the advancement of their goals. They discuss their findings of the various student bodies that are represented in the data, address the data’s deficits, and identify meaningful uses of the results that will support all students.

UNE’s academic programs and colleges and co-curricular units and divisions participate in an annual assessment process. Each year, they complete the University Assessment Committee's report forms and share their findings with their respective areas, as well as with the assessment and provost offices. The annual report forms are grounded in questions from NECHE’s comprehensive evaluation e-series forms and the University Assessment Committee’s charge to track and report on the annual assessment data.

Learn more about UNE’s annual assessment reporting process

For guidance on completing the annual report, refer to the following documents.

Internal and External Support

- AAC&U’s Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education (VALUE) Rubrics

- American Evaluation Association

- ASSESS listserv

- Association for Institutional Research (AIR)

- Association for the Assessment of Learning in Higher Education (AALHE)

- Grand Challenges in Assessment in Higher Education

- IUPUI Assessment Institute

- Learning Improvement Community

- National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment (NILOA)

- New England Educational Assessment Network (NEean)

- North East Association for Institutional Research (NEAIR)

- American College Personnel Association-College Student Educators International (ACPA)

- ACPA’s Commission for Assessment and Evaluation

- Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education (CAS)

- National Academic Advising Association’s (NACADA) Assessment Resources

- National Association of Student Personnel Administrators (NASPA)

- Student Affairs Assessment Leaders (SAAL)

- Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education

- Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy, and Practice

- Assessment Review

- Assessment Update

- Assessment Writing

- Educational Assessment

- Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Accountability

- Emerging Dialogues

- Intersection: A Journal at the Intersection of Assessment and Learning

- Journal of Assessment and Institutional Effectiveness

- Journal of Educational Measurement

- Journal of Student Affairs

- Journal of Student Affairs Inquiry, Improvement, and Impact

- Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice

- New Directions for Teaching and Learning

- Research and Practice in Assessment