Regina Dyer ’26 has spent her summer working to preserve some of the nation’s most iconic maritime beacons — and ensure they endure the lasting effects of climate change

Maine’s lighthouses carry deep historical and cultural significance. From the early days of maritime trade, these beacons have guided ships carrying goods to fuel commerce, nourish lives on land, and ensure a flourishing coastal economy.

But today, these iconic structures face a different kind of threat, not from fog or shipwreck, but from the escalating effects of climate change.

Regina Dyer (Environmental Science, ’26), a rising senior at the University of New England with a minor in geographic information systems (GIS), is working to preserve Maine’s lighthouses from the perils of rising seas, intensifying storms, and shifting shorelines.

Through a UNE Sustainability Fellowship and combined internship with the Maine-based American Lighthouse Foundation, Dyer is developing climate change vulnerability assessments for more than a dozen lighthouses up and down Maine’s rocky coast.

Left: Regina Dyer pilots an amphibious boat through the Casco Bay. Right: UNE Trustee Ford Reiche, owner of the Halfway Rock Light Station.

Dyer spends most of her summer days in UNE’s GIS Lab building detailed storm surge maps using ArcGIS software. These digital maps model projected sea level rise by combining mean high water data with storm surge scenarios of two, four, and six feet.

In many cases, Dyer said, especially at offshore or low-lying stations, a four-foot surge could submerge critical infrastructure. A six-foot surge could overtake entire islands.

“I want to spread awareness about how vulnerable these lighthouses really are,” Dyer said. “People think of climate change affecting homes, not necessarily lighthouses. But these are some of Maine’s oldest structures, and they weren’t built to withstand what we’re seeing now.”

Her final product will be a story map hosted online and shared with both the American Lighthouse Foundation and the public. Each lighthouse featured includes a data visualization of its risk level, along with a narrative description Dyer has written to explain the site’s unique vulnerabilities, from building materials and age to past weather damage and storm exposure.

Left: Halfway Rock Light Station from Casco Bay. Right: Seabirds resting at Halfway Rock.

Dyer’s work has taken her to some of the most remote and revered sites on the Maine coast, from Portland Head Light in Cape Elizabeth to the Little River Light Station on the coast of Cutler, far Downeast. Each week, she travels to a new location, documenting conditions, interviewing site stewards and harbor masters, and learning how communities are working to maintain these beacons against increasingly tough odds.

On a recent morning in late July, Dyer paid a visit to Halfway Rock Light Station, a granite tower perched on a ledge 10 miles offshore, in the middle of Casco Bay.

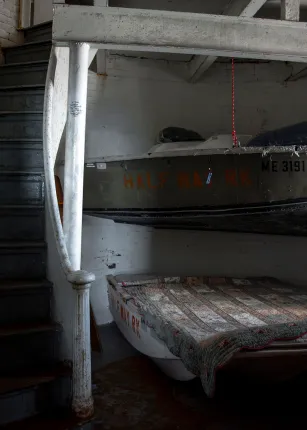

Built in 1871 and long considered one of the most dangerous “stag stations” for lighthouse keepers, Halfway Rock was abandoned in 1975 and left to deteriorate for decades, its dock torn away by storms, birds nesting inside, and water leaking through every level of the structure.

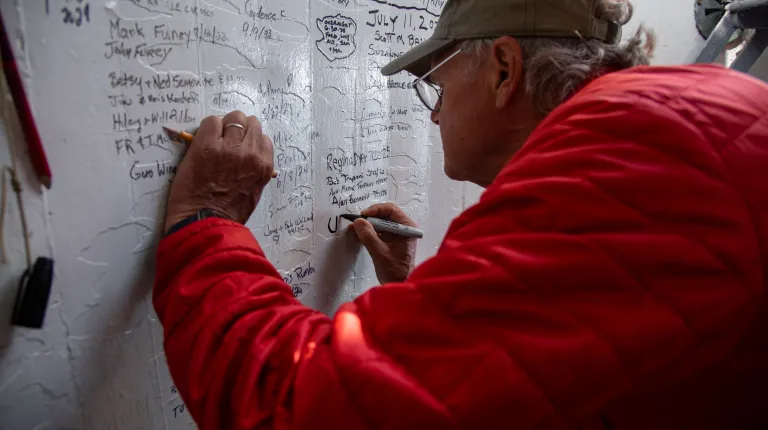

In 2014, when the government could not find a nonprofit to assume responsibility for the site, the site was purchased by Ford Reiche, J.D., an entrepreneur, preservationist, and member of the UNE Board of Trustees. Reiche led a full-scale restoration of the property and its corresponding lighthouse, which earned the American Lighthouse Foundation’s highest award in 2017.

Reiche personally led Dyer’s visit to Halfway Rock, sharing the site’s history and the extensive resiliency work he has undertaken to fortify it against future environmental threats.

“Being out there with Ford and hearing how he brought Halfway Rock back was incredible,” Dyer said. “It reinforced my understanding of what climate resilience can look like in practice and how much effort it really takes.”

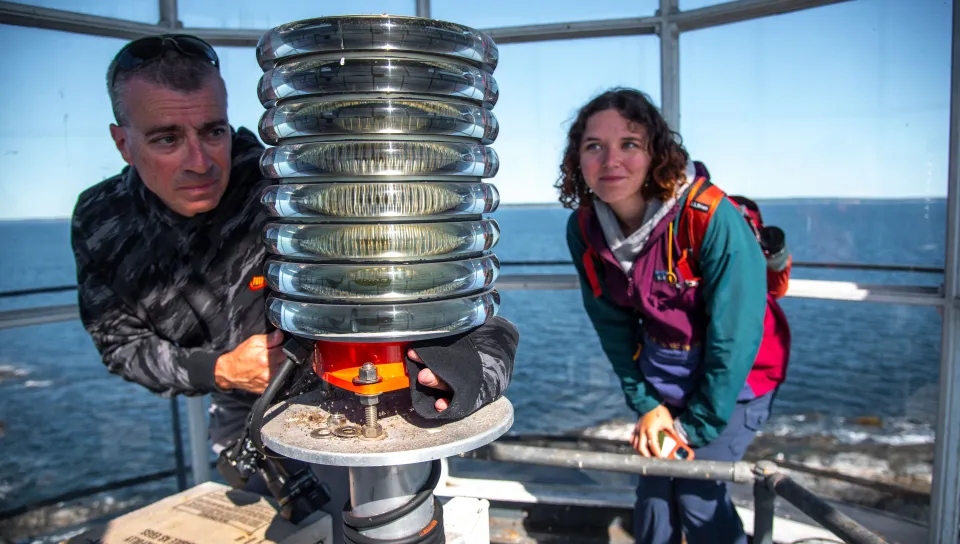

(Clockwise, from top left): Bob Trapani Jr. and Dyer examine the lens of Halfway Rock; Dyer, Reiche, and Trapani pose with Ann-Marie Trapani, associate director of the American Lighthouse Foundation; Reiche marks the date of the trip on the lighthouse walls; the lighthouse keeper’s quarters; and Reiche shows Dyer details of the lighthouse.

Reiche said it is “inspiring” to work closely with a UNE intern on the challenges presented by climate change.

“Regina displays the passion we want to see in our experts of the future,” he remarked. “The American Lighthouse Foundation is at the forefront of this work as it pertains to preserving our historical aids to navigation, and I know firsthand that this UNE internship has contributed to that body of work.”

Dyer’s work is being mentored by Bob Trapani Jr., executive director of the American Lighthouse Foundation. The fellowship’s experiential structure enables Dyer to conduct field work, build GIS datasets, and help lay the groundwork for preservation strategies in a warming climate, which Trapani said will be foundational in protecting Maine’s lighthouses from the adverse effects of climate change moving forward.

“After two-plus centuries of safeguarding humanity along the Maine coast, it is now our turn to save lighthouses from the harm being caused by climate change,” Trapani said. “Ensuring Maine’s lighthouses are made more resilient in the face of this perilous threat requires a team effort.”

Trapani said the contributions Dyer is making to the cause, in further collaboration with the World Monuments Fund, will resonate for years to come.

“Through her leadership in this initiative, Regina is a bright light for Maine’s lighthouses when they need it most.”

Left: Dyer peers into the lantern room of Halfway Rock Light Station. Right: Dyer smiles at the dock.

Dyer’s work is also deeply personal. Though she grew up in Massachusetts, both of Dyer’s parents are from Maine, and lighthouses have been part of her life since childhood.

As an adult, Dyer is using the skills afforded to her by UNE’s experiential approach to help solve one of coastal Maine’s most pressing challenges: protecting the past while preparing for the future.

“Nothing gets more ‘Maine’ than a lighthouse,” she said. “I want to help make sure these lighthouses are still standing for the next generation to see. Preserving them is part of preserving Maine’s identity.”