How a Campus Dig Unearthed New Professional Pathways

by Alan Bennett

It started with a photograph on the wall.

A framed aerial shot of the University of New England’s Biddeford Campus, taken in 1954, was hanging idly in an office in Decary Hall.

The picture went largely unnoticed until UNE faculty members Arthur Anderson, Ph.D., and Eric G. E. Zuelow, Ph.D., spotted it, a recognizable, yet curious scene: a pond where a parking lot now resides, and a house, long gone, perched near where Decary now stands.

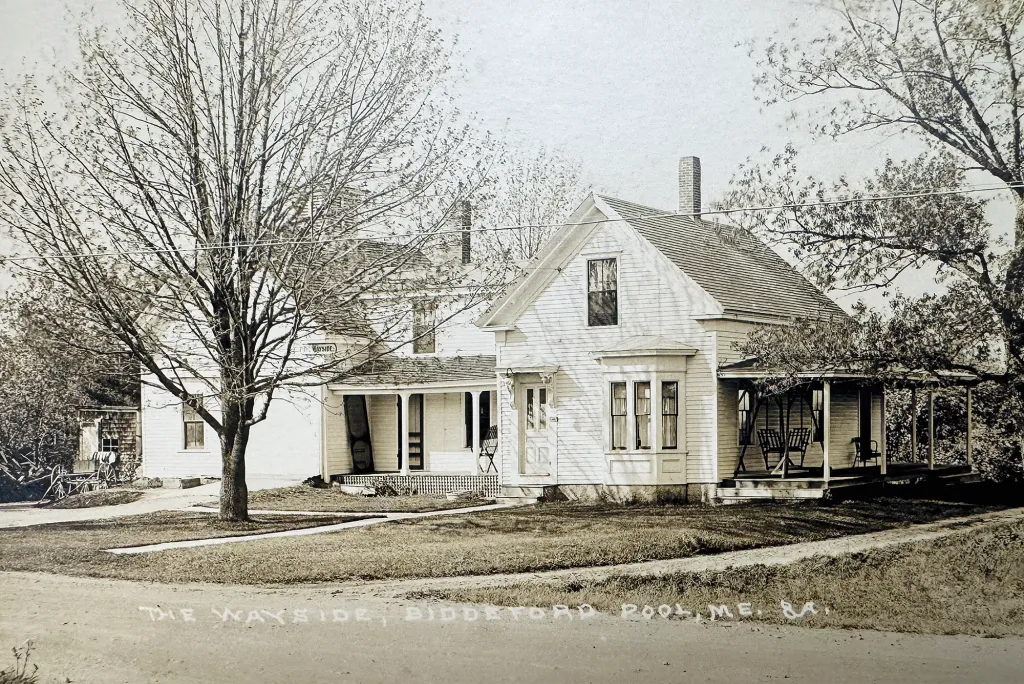

That house, they came to learn, was called The Wayside, and archival documents revealed it once operated as a shore dining hall during Maine’s early tourism boom. Later purchased by the Franciscans in 1948 for use by St. Francis College, it was razed in 1963 to make way for a growing campus that would eventually become the UNE we know today.

The site, Zuelow mused, was virtually crying out for study.

This one photo would drive Zuelow and Anderson to collaborate across their respective areas of expertise in cultural history and archaeology to offer a jointly taught course seeking to uncover The Wayside’s story — literally, figuratively, and across disciplines — and construct a living archive of this piece of UNE’s past.

Uniting the skill sets of students from the University’s programs in archaeology, history, business, environmental and marine sciences, and psychology, the course was built around the belief that we better understand where we’re going — personally, professionally, and societally — by examining where we’ve been.

And, guided by the vision that no single discipline could accurately or completely tell The Wayside’s story, students uncovered more than just relics of former lives. In the soil beneath their feet and through the spirit of collaboration across academic aisles, they took home lessons that shaped their own lives as well.

Time Team New England

On a warm September afternoon in 2024, a group of students knelt in the grass outside Decary Hall, carefully moving down through layers of soil, millimeter by millimeter. With trowels and sifters, they uncovered bits of brick, fragments of glass, and weathered nails: small, tangible pieces of the building that once stood on this spot.

The group had spent weeks preparing for this moment, but the dig itself wasn’t the sole focus of the class, which the professors dubbed “Time Team New England.” Rather, Anderson said, it was the means through which students could learn from each other rather than alongside each other in approaching a shared question from multiple angles.

“We weren’t simply after artifacts,” said Anderson, an associate teaching professor in the College of Arts and Sciences. “We were after understanding, to see how different perspectives, different kinds of expertise, could shape the questions we asked and the answers we found.”

Allied Learning, Applied Outcomes

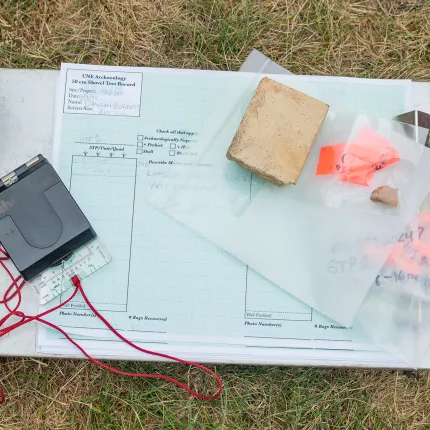

Following historical maps and guided by utility scans, the students carefully marked 50-by-50-centimeter test pits and then began digging, layer by layer.

Early finds — window glass, brick fragments, clam shells, and rusted screws — may have looked unremarkable to those passing by. But to the students, these were artifacts that told a deeper story: Some items suggested phases of domestic life; others taught lessons that went beyond physical limits.

Indeed, the course illuminated UNE’s institutional journey from a cluster of buildings to a modern university, intentionally leveraging its rich history as a community hub to foster connections and collaboration across students from all academic walks of life.

In his teachings, Anderson said, this diversity isn’t incidental; it is essential and purposeful.

“Archaeology is the ultimate interdisciplinary experience,” he remarked. “It’s not just about digging. It’s about interpreting, and that’s where every student’s lens adds value.”

That value was evident even before the dig began.

As Zuelow’s history students sank into the archives, others from UNE’s majors in marine and environmental studies used their expertise in remote sensing, scanning the ground with drones and other tools to identify the most promising plots to till.

Throughout the semester, students from UNE’s communications and media arts program employed their journalistic skills, breaking out boom microphones and using their phones to record digital field notes and document the team’s discoveries.

The group’s individual outputs converged in one collective final project: a multidisciplinary archive of The Wayside — complete with photographs, spatial maps, and a series of student-produced podcasts — entitled “Falling By The Wayside.” Their data will feed into a permanent record of the site for future students to expand through their own interdisciplinary explorations.

This model of learning across boundaries, solving problems in teams, and engaging with real-world questions is at the core of UNE’s educational philosophy, wherein students discover new academic interests and career trajectories they might not have considered without opportunities for such collaborative learning experiences.

“With interdisciplinary learning, there’s a decentralization of power and letting students take the lead,” Anderson said. “Neither Eric nor I could have tackled this problem alone by working in our own silos. We needed student help, and, in turn, our students became attuned to understanding the limitations of their own individual approaches and the strengths of their peers’.

“Everyone’s presence and input were vital to this project working,” he added.

Grounded in Integrated Learning

Courses that challenge conventional pedagogies by prioritizing innovation across academic specialties are increasingly common at UNE.

In late 2024, as Anderson’s and Zuelow’s students shifted their focus from the dirt to their desktops, two professors from UNE’s political science and philosophy programs led a class of students analyzing the rhetoric, ethics, and progress of the U.S. presidential election in real time, including through election night.

These are not one-off projects, said Amy Keirstead, Ph.D., associate dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. Interdisciplinary experiences at UNE are deliberately designed to ignite curiosity and carve professional pathways for students, including internships and peer-reviewed research.

“By intentionally connecting students with faculty and colleagues outside their own fields, our students emerge from their undergraduate programs well equipped for postgraduate work or to enter the workforce directly, having already worked in interdisciplinary teams, and able to approach complex problems from multiple lenses,” Keirstead said.

For Anderson, this is the heart of the work.

“Whether they go into archaeology, business, health care, or any other field, the ability to collaborate, to listen, to integrate different viewpoints, that’s what will make them successful,” he said.

A Foundation for the Future

Whether excavating a historical site, evaluating policy in an election year, or launching a new product, these collaborative experiences endow students with more than just basic knowledge. Students also are learning to work together to manage uncertainty and adapt to new challenges, skills Zuelow said are essential to working in a rapidly evolving world.

“If you’re going to succeed in the workplace and in life, you have to learn how to solve problems with people who see the world differently than you do,” he said. “That’s what this class was about.”

Meredith Bailey (Psychology, ’26) enrolled in the course to better understand human relationships in preparation for her career as a future clinical psychologist.

Bailey said the insights gained from interacting with her peers with majors from history to hard science to health care gave her the skills necessary to navigate the myriad interactions she is already facing in her young professional life, providing a blueprint for her work as a mental health technician at Parkland Medical Center in Derry,

New Hampshire.

“My classmates and I had different backgrounds and focuses within our studies, and having the skills to work with multiple disciplines at once reflects those same social dynamics and will be useful once we graduate,” said the senior from Hampstead, New Hampshire.

Bailey’s working environment, being surrounded by and collaborating closely with physicians, psychiatrists, nurses, and other clinicians — as well as patients from all walks of life — serves as a living, breathing representation of those classroom experiences.

“Working at the hospital, I interact with patients of diverse backgrounds and can see how working in the psychology field does not include only psychology — it is inherently interdisciplinary,” Bailey said.

She said that, for her and her peers, the course was the first time they felt that academic learning directly translated into real-life work, equipping them with meaningful interdisciplinary experiences that will shape their professional pathways upon graduation.

“This course taught me more about taking charge in my learning and my future career,” Bailey said. “This was not just a regular course. We were making a difference.”

Zuelow said that, through bridging disciplines and combining their expertise, Bailey and her peers ultimately uncovered his and Anderson’s true purpose for designing the course in the manner they did.

“History and archaeology are founded on different principles, but when they come together, the two disciplines create an idea of belonging in a place and a sense of being part of it,” Zuelow said, noting that UNE is now carrying forward the legacy of its precursor institutions.

“Students may not necessarily be conscious of that at first, but if they really feel like they’re part of something bigger, I think that matters,” he added. “If we, as instructors, can create a sense of belonging for our students and continue that legacy, the more powerful the story becomes.”

Bonus Content

Podcast: Journeys into the Past at UNE

Students document the interdisciplinary excavation of The Wayside, a former dining hall that reveals UNE's evolution from St. Francis College to the modern University seen today.