Interprofessional Simulation Prepares Students for Team-Based Care

by Emme Demmendaal

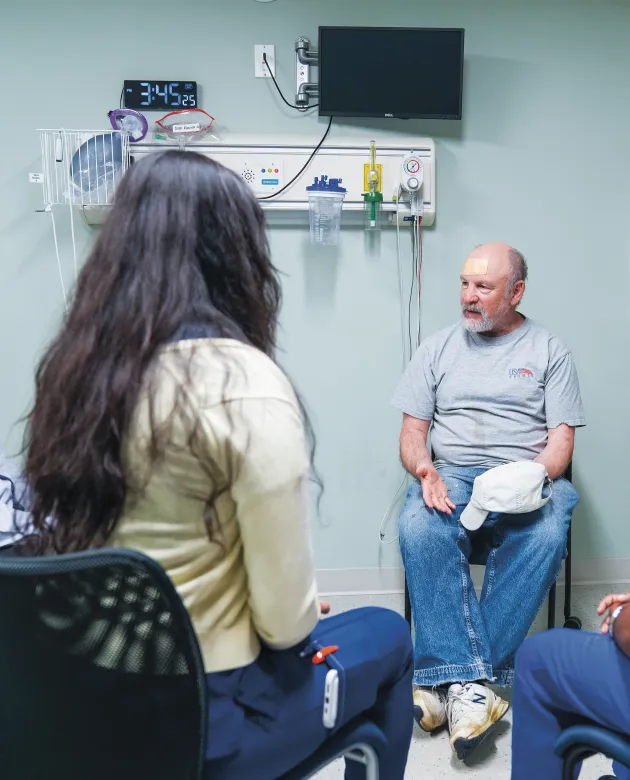

Meet “Michael.”

He’s a 74-year-old rural Mainer who has made it to the clinic with several health concerns.

But don’t expect to run into him on Main Street in a small town like Saint Agatha, Maine.

Instead, Michael is a case study brought to life by a trained patient actor at the University of New England’s Interprofessional Simulation and Innovation Center (ISIC) on the Portland Campus for the Health Sciences.

With a distinct Maine accent and several realistic health issues, Michael represents the kind of patient UNE students will one day serve and is the centerpiece of interprofessional learning cases for future health care workers.

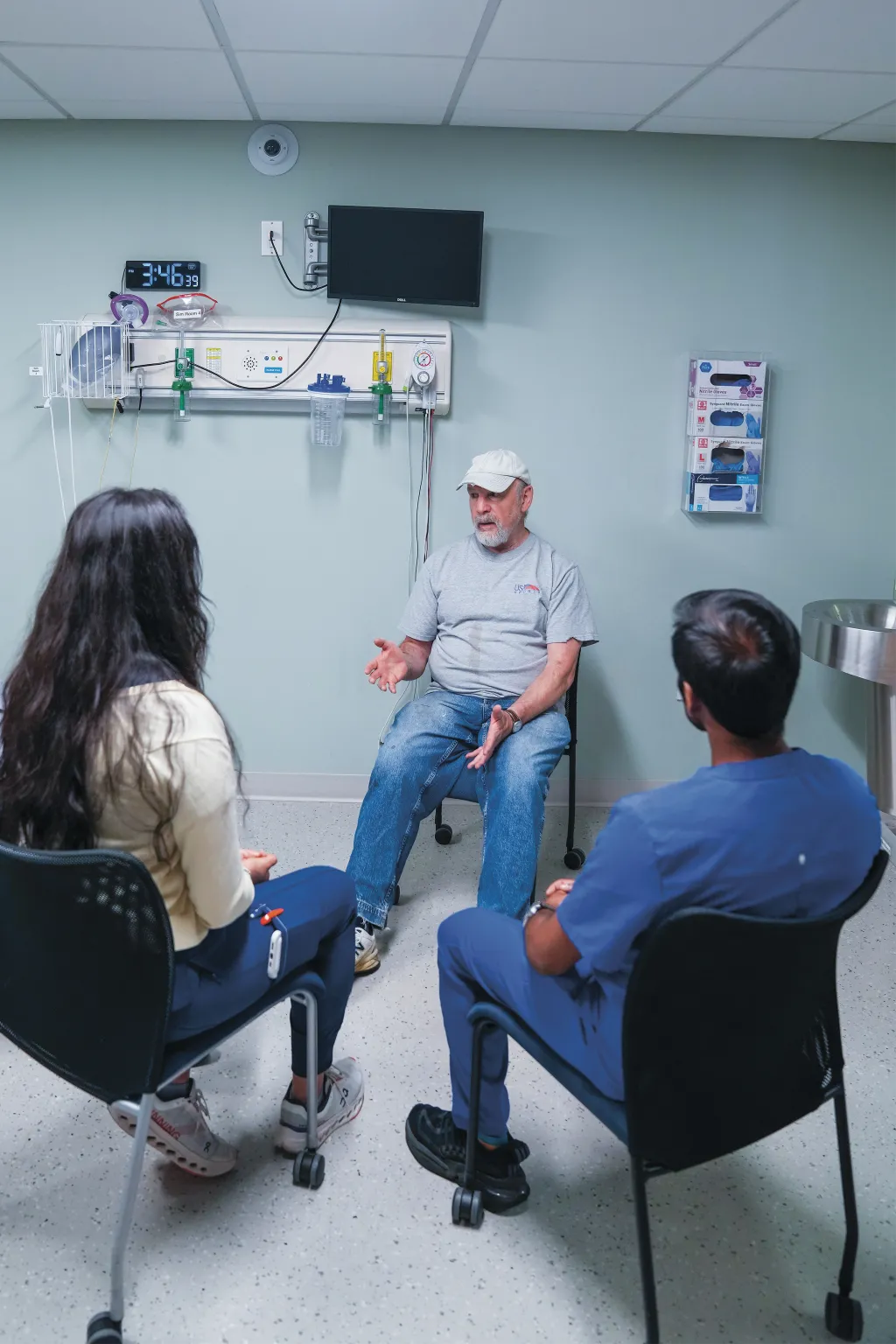

Students on the state’s only integrated health education campus work together in interprofessional teams — a form of interdisciplinary collaboration specific to health care education and practice where students learn from, with, and about each other across disciplines — to assess Michael’s complex health needs and create comprehensive treatment approaches that draw on each profession’s expertise and perspective.

In the center, students develop their collaboration and teamwork skills before entering clinical settings, said Ashley Buckingham, M.S.N., R.N., senior director of ISIC.

“Students get the chance to practice what they’re learning in the classroom and apply those skills in a safe environment, being able to make mistakes and deeply reflect on things they can improve upon when they enter clinical practice,” said Buckingham, who is a certified health care simulation educator.

With older adults being the fastest-growing segment of the U.S. population and Maine being the oldest state by median age, the Michael Case represents the reality that more than a quarter-million Mainers over 65 will need comprehensive, coordinated care — the kinds of complex cases that require multiple professional perspectives.

“The evidence is clear,” said John Vitale, Ph.D., UNE associate provost for Interprofessional Education and dean of the Westbrook College of Health Professions, noting that recent studies show positive impacts of an interdisciplinary team-based approach on everything from patient satisfaction to mortality rates. “Effective interprofessional education improves health outcomes, and here in Maine, where patients often travel long distances for complex care, we have a responsibility to ensure our graduates can collaborate seamlessly from day one.”

Effective interprofessional education improves health outcomes, and here in Maine, where patients often travel long distances for complex care, we have a responsibility to ensure our graduates can collaborate seamlessly from day one.”

— John Vitale

This is a fact that Alexa Lanteri ’26, a student in Maine’s first yearlong accelerated nursing program, found important as she went through the Michael Case in July.

“Details woven into the case reflect the person behind the health concerns,” said Lanteri. “Michael was very hardworking and independent, so we had to ask ourselves: Is this care plan realistic for someone with his personality?”

The case, launched in 2019, was developed by a committee of faculty representing UNE’s 14 different health professions, and it is now offered multiple times a year.

“It reflects the expertise of clinical content experts across all of our health professions here at UNE,” Buckingham said, adding that the case study is continuously refined to challenge students.

Betsy Cyr, D.P.T., an assistant clinical professor in the Department of Physical Therapy, who helped develop and facilitate the case, explained that the University takes a systematic approach to crafting realistic health care scenarios.

“There is intention and design in how it’s created, so that we can really address those interprofessional collaboration and communication competencies,” she said. “The authenticity is really valuable, so students get hands-on experience that readies them to appreciate what health care looks like in the real world.”

And most importantly, each health profession has a key role in the Michael Case.

Unlike other case studies that are developed for students in a single profession to practice discipline-specific skills, the Michael Case brings together different groupings of students from multiple health professions who must collaborate to address complex patient needs that no single discipline can solve alone.

The interprofessional case creates unique dynamics based on the student participants, Buckingham explained. “Each time we’ve run this, it’s always a little bit unique and different based on the students who are in front of you,” she said.

For example, one group might include students in occupational therapy, nursing, pharmacy, and osteopathic medicine, Buckingham noted, while another grouping may include students in UNE’s dental medicine, physical therapy, and physician assistant programs.

Cyr said the small group sizes and the variety of professions each time the simulation is run are assets to the learning experience.

“Health care isn’t done in a cookie-cutter fashion, but we can address interprofessional priorities through case studies like Michael’s, which is really valuable,” she said.

Varun Kota ’29, a first-year medical student in UNE’s College of Osteopathic Medicine, the only medical school in Maine, said he learned that other disciplines knew much more beyond their narrow specialties.

“It surprised me,” said Kota, who is from Virginia, noting that a fourth-year Doctor of Dental Medicine student knew drug reactions and pointed out potential nutritional concerns for Michael. “There is a lot more that different professions can do than what appears on the surface.”

For students like Kota, it’s their first time working on an interprofessional team in an academic setting.

“We were all working together, making sure that we were covering each other’s bases and doing our best to take care of Michael,” he said.

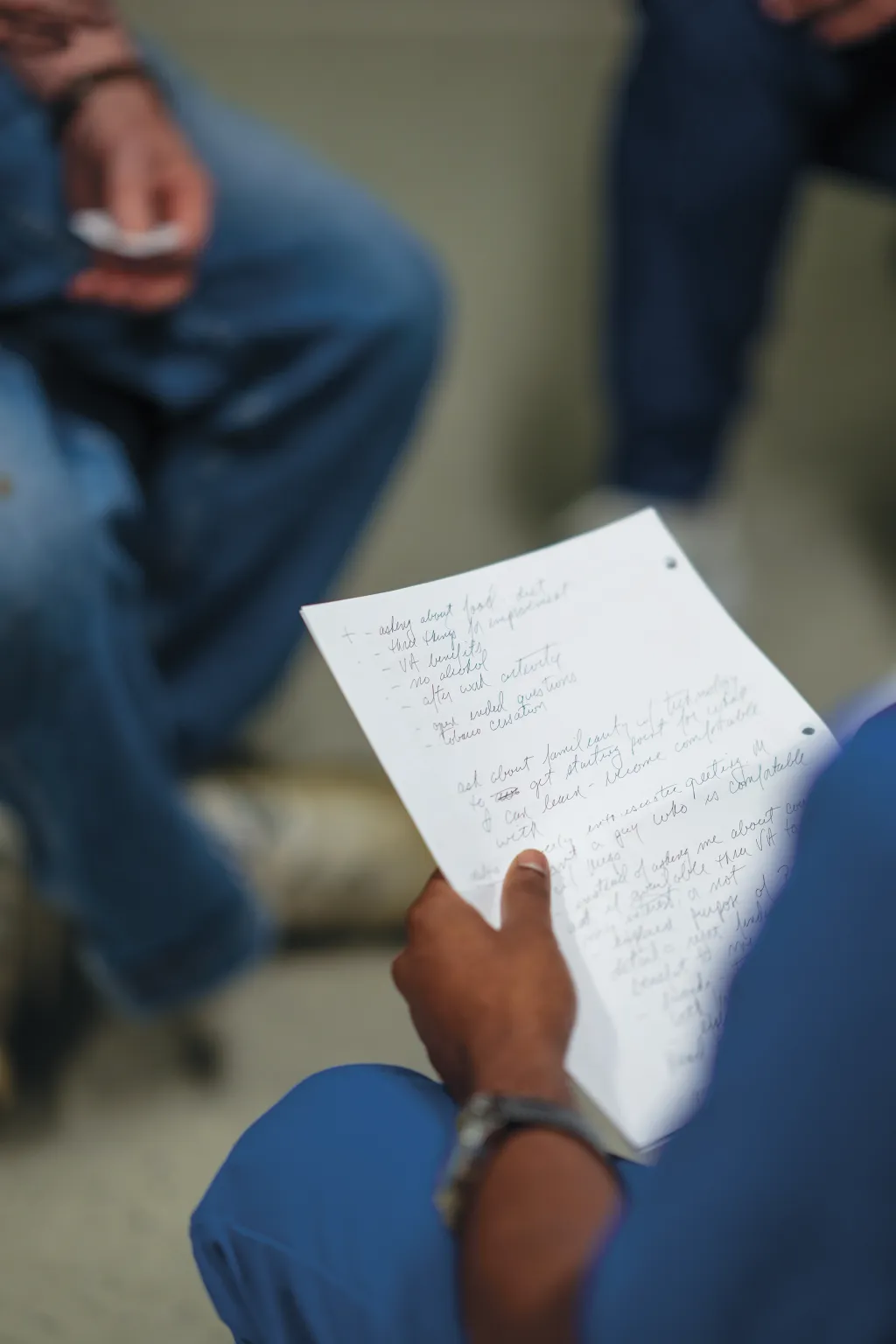

Students enter the case with very little information, Cyr explained, and it’s expected that they will pull out key information from the standardized patient as a team.

The case follows a structured cycle that mirrors real clinical practice. Teams of three to five students interview the patient and then debrief together with faculty facilitators to analyze the findings and plan their next steps. They return for focused follow-up interactions to gather additional information and develop comprehensive care plans.

“Michael’s case is complex and holistic, and we have to keep it patient-centered,” Cyr said. “No one role can manage Michael’s needs alone.”

The iterative process teaches students that effective health care requires continuous assessment, team consultation, and adaptive planning, she said.

The skills learned in the Michael Case translate directly to better patient care, fundamentally changing how Jasmin Gil ’26, a UNE accelerated nursing student from Florida, approaches her clinical rotations and patient interactions.

With the student team, Gil found herself in discussions about the patient’s lifestyle habits that revealed unexpected layers of complexity. The interprofessional dialogue helped the team understand how different health behaviors can serve multiple purposes, some beneficial, others potentially harmful.

“We were able to talk about it on a professional level, come to an agreement, go back and ask Michael more questions, almost like we were playing detectives,” Gil reflected.

During the patient interview process, one of the students asked Michael to identify three personal goals for seeking care that day — what Michael hoped to achieve from his visit rather than what the health care providers assumed he needed.

It was a question that shifted the entire team’s perspective, Gil said. It demonstrated an understanding of the patient’s priorities and motivations before developing a treatment plan. The approach exemplified a core principle of effective health care: meeting the patient where they are, she said.

“It just broadened my perspective and mindset when it comes to a patient,” Gil noted, adding that she used the same question the very next day in the clinic. “It helped me see the patient as a whole, from different areas of health care, rather than just my area of focus.”

Research supports what UNE students experience firsthand. In fact, a recent study led by UNE’s own Center to Advance Interprofessional Education and Practice (CAIEP) found that 81% of interprofessional education graduates work on such teams after graduation, and 80% report that their IPE experiences significantly impacted their practices in positive ways.

Health care collaborations that emphasize care coordination show the highest proportion of significant effects on clinical and patient-related outcomes, said CAIEP Director Kris Hall, M.F.A.

“Better relationships improve everyone’s experience of health care,” Hall remarked. “Interprofessionalism both supports the development of teamwork skills employers seek and prepares students for success in diverse professional environments. The Michael Case represents just one example of interprofessional education in action at UNE.”

Because of the case’s popularity, the committee is expanding its offerings to include “Lucy,” a younger female patient with a different set of health care challenges. The Lucy Case is currently in development and is scheduled to be rolled out this academic year.

Additionally, in each of UNE’s health professions programs, interprofessional education, or IPE, is built into the curriculum rather than offered as an elective.

For example, each spring semester, a pediatric interprofessional simulation is offered that has grown in recent years from 70 students and two health professions to 130 students and three health professions. The full-day, intensive experience includes students in physical therapy, occupational therapy, and nursing, working with children, ages 6-12, and faculty members playing parents in realistic hospital scenarios.

The simulation is so authentic that nursing students receive clinical credit for their participation, Cyr said.

Beyond formal simulations in the ISIC, interprofessional learning happens through peer-to-peer teaching opportunities. In one initiative, College of Dental Medicine students teach physician assistant students about oral health screenings and fluoride varnish application, sharing expertise that PA students might not otherwise encounter in their traditional curriculum.

Essie Love, a fourth-year dental student from Pennsylvania, participated in both the Michael Case and this teaching initiative. For Love, who has earned an honors distinction in interprofessional work, these collaborative learning opportunities have shaped her entire approach to health care.

“Prior to coming to UNE, I never realized how beneficial it could be for other professions to collaborate together,” she said. “It’s really shaped a new goal for me as a provider; one day, I’d love to have an interprofessional event in my own community.”

UNE’s approach draws strength from something most universities cannot replicate: all health professions co-located together on one campus.

“I think it helps me as a student because (UNE) prioritizes interprofessional collaboration and care throughout all of the programs,” added Lanteri. “They really help you build those skills to work well with others.”

This advantage has positioned UNE as a leader in interprofessional education, an approach that research has shown to produce measurable improvements in patient outcomes. Studies demonstrate that 96.7% of patients appreciate collaborative atmospheres when health care teams work together effectively, while 89% of research studies show statistically significant improvements in attitudes toward team-based patient care.

As health care becomes increasingly complex and team-based, UNE’s approach to interprofessional education — anchored by cases like Michael’s — prepares graduates who can collaborate effectively from the

start. In Maine, where rural populations face significant challenges in accessing quality health care, these skills represent essential tools for improving community health outcomes.

Michael may not be real, but the collaborative care skills he helps students develop certainly are. For the patients these graduates will eventually serve, that will make all the difference, Kota reflected.

“I’m working with these different professions because we all have a shared understanding of medicine from different perspectives,” he said. “This was what medicine is meant to be.”