UNE Summer Sustainability Fellows Create Impact Through Community Alliances

by Jen A. Miller, freelance writer

Through a broad spectrum of community alliances, University of New England Summer Sustainability Fellows are creating tangible impacts while building more resilient communities.

The path toward a more sustainable world will not come from just one direction. Academia can’t do it alone, nor can private companies, nonprofits, or governments at any level.

Instead, collaboration is required, with people across different types of organizations and disciplines working together to create sustainable solutions for real-world challenges.

That’s the basis of the UNE Summer Sustainability Fellowship program, which partners UNE students and recent graduates from majors across the University — environmental and marine sciences, health professions, business, the humanities, and others — with community members who have tangible sustainability-related goals and ambitions.

In its first year, the program had six fellows over 10 weeks; in 2025, that number has grown to 16.

For local communities, the UNE Sustainability Fellows help organizations address projects that may have been on the back burner, whether because they hadn’t had the budget to address them or they couldn’t find the right person with the right skills to tackle the job.

“It’s really difficult to be able to balance economic well-being, social well-being, and environmental health on any project. To go out and practice this in the real world is a really humbling experience,” said Cameron Wake, Ph.D., director of UNE North, the University’s Center for North Atlantic studies, which examines the Arctic and North Atlantic regions through an integrated, planetary approach encompassing environmental, economic, and health-focused perspectives.

But at the same time, Wake said, that experience is an important one. For UNE students, the fellowship is a way to take classroom lessons out into the real world and work with professionals from other fields on solutions that would not have been possible without diverse knowledge and expertise.

“When you do it as part of an effort that is well supported and well scaffolded, it really helps the student understand that they can make a difference,” he said, noting that each project is designed to build connective tissue between different areas of expertise. “I am beyond convinced that, in order to address really big challenges … (this work) has to be done in an interdisciplinary way.”

Keeping a Lighthouse Alight

The impact UNE Sustainability Fellows are making extends from the inner city to the salty sea and from the state’s largest community into the Gulf of Maine.

The Goat Island Light Station is a local institution. The lighthouse, completed in 1835, sits on an island about a mile offshore of Kennebunkport’s Cape Porpoise Harbor and was designed to help mariners find their way through dangerous rocks, a job it’s still doing today.

But it’s not cheap or easy to run a lighthouse, especially one that has living quarters for lighthouse keepers and can be accessed only by boat and kayak (and even then, only on days when the weather cooperates).

With the Gulf of Maine warming faster than the majority of the world’s oceans, climate change threatens Goat Island, too, as rising sea levels and intensifying storms put everything there, including the lighthouse, at risk.

In her fellowship, Annika Doeppers (Marine Biology, ’25) brought her understanding of marine ecosystems to work with facility managers to develop a new operational and marketing plan for the lighthouse, maintained by the Kennebunkport Conservation Trust.

The trust has preserved 3,000 acres of land so far, but the Goat Island Light Station is unique because of where it is. The trust has management plans for most of its inland properties, for which Doeppers began work on her management plan, and then adapted it for an island.

A typical management plan, Doeppers said, focuses on forest space, so she’s changing it to beach space, where it’s “less about trees and more about sea creatures.” She identified coastal environment vulnerabilities such as non-native grass growing on the island, while trust staff provided insights on building management practices to preserve the station.

The plan also addresses the unique challenges of a property that is about a mile offshore and is also being taken care of by people who live there. “It’s a way of making sure there’s a solid plan for communication between the keepers and the trust,” she said.

Ensuring that the lighthouse continues to operate has both functional and morale purposes.

“This lighthouse is a pillar to its community,” she said, not just because it’s a critical piece of safety infrastructure for Cape Porpoise Harbor, which is an active fishing community. It’s also a symbol of the surrounding area, she said, and an important historical touchstone.

“It’s important that it stays out there for as long as possible, guiding people through the harbor,” she said.

Getting Granular on Pollution Sources

Big data can be a powerful thing, providing insights that can make differences in people’s lives. But big data only works if it’s put to good use, meaning that it’s formatted and incorporated in a way that it can be analyzed and visualized to provide helpful and accurate results.

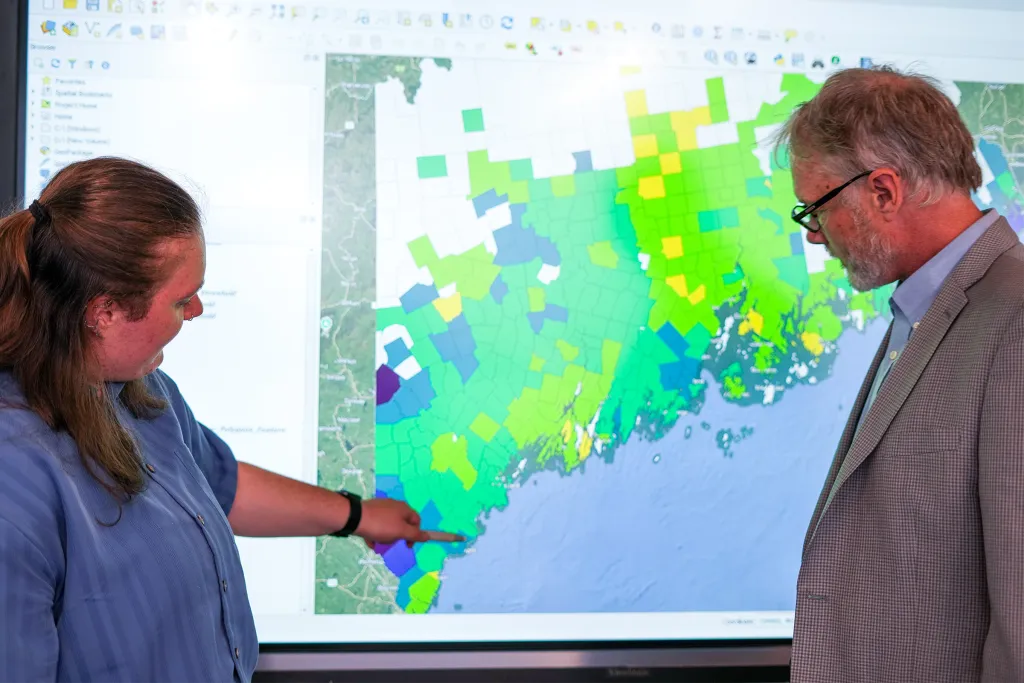

That’s especially true when it comes to public health, said Ruth Ellis ’25, who is using her studies as an environmental science major to inform community health outcomes related to pollution.

Apriqot’s data analytics solution already uses information from public health agencies, health systems, foundations, and community organizers. Ellis worked on expanding those sources, with a focus on water pollutants, including data from lead tests at 700 Maine schools and tests for PFAS — so-called “forever chemicals” known to increase cancer risk, cause fertility issues, and have other detrimental impacts on human health — done at 100 Maine schools.

In her fellowship, Ellis is working with data experts at Apriqot, a two-year-old, Portland-based startup, on a computer analytics framework that uses her background in environmental studies to enable pollution-related data to be incorporated into the company’s models so its data sets can provide quality, localized demographic and health metric data.

“Since they’re a startup, they don’t really have environmental context for their models yet,” said Ellis, who will graduate in December.

But Ellis didn’t just build up data sets and leave it at that. Instead, she’s built a system that is purposely not pollutant-specific. That way, Apriqot can add more environmental data as it becomes available, to address local health concerns better and in a timelier manner.

“The company will be able to partner with people who work in the realm of PFAS or lead, or whatever environmental data they want to use, and incorporate it,” Ellis said, adding that “this is the beginning for them, so that they can partner with organizations to understand where these pollutants are and who is being impacted by them the most.”

Creating a Blueprint for Better Urban Gardening

Cultivating Community is a long-running Portland nonprofit that focuses on food justice through programs that prioritize people who may not have access to fresh fruits and vegetables. One prong of its work is running community gardens across the city, including the Boyd Street Urban Farm, which includes a “pick-as-needed” orchard that grows apples, pears, peaches, cherries, and raspberries.

One persistent issue, though, has been the health of the trees, which don’t produce as much fruit as they should.

In his fellowship, Luke Jenkins (Biology, ’26) has been tasked with practical horticulture duties, including orchard care and composting, for Boyd Street, as the farm is familiarly known.

“This is one of the few green spaces (in Portland) that is a safe haven for everyone and for people to come and spend their day,” said Jenkins, who calls himself “a big plant guy.”

“When it comes to the garden, it’s a good opportunity for people to have food,” he said. “It doesn’t matter who you are. If you need the food, take as much as you need.”

To create a more fruitful orchard, he spent his fellowship collaborating with ReTreeUs, a nonprofit that helps plant trees and promote education, along with arborists and orchard owners in the area, to compare what they’re seeing in terms of invasive species and horticultural diseases and get ideas on how to increase fruit yield at Boyd Street.

From there, Jenkins created an action plan — translating the expertise he’s gained from in-class lessons into impactful, hands-on work — that can realistically be implemented at the garden.

One problem, for example, has been burdock, a pesky weed with burs so sticky that they inspired Velcro. Jenkins couldn’t simply order gardeners to remove these plants, but he could work with Cultivating Community to educate gardeners as to why this weed is a problem and what steps they can take to prevent its spread.

He also worked on a composting system that will be more efficient for the garden, with better signage about what can be put into each container while also stressing the importance of respecting the space.

Jenkins hopes that his plans at Boyd Street can be replicated across Cultivating Community’s other sites, for the sake of both the health of the gardens and the community.

“If you’re hungry and you can’t find food or can’t afford food, you can come to our orchard and pick that peach or pick that apple,” Jenkins said. “If you need it and you have (access to) it, that’s a kind of security, knowing it’s there.”

He added that integrating his plant science knowledge with insights from arborists, orchard managers, and community educators to create a practical action plan for the orchard has been an important part of the experience.

“It’s pushed me to become more thoughtful about how I communicate, how I adjust to different priorities, and how I make sure the work aligns with the needs and values of the communities it’s meant to support,” he said.

Moving the Needle Forward

As the last traces of summer fade on Maine’s coast, the impact of UNE’s Summer Sustainability Fellowship ripples far beyond campus. The fellowships show what’s possible when students step beyond the classroom and work beyond their academic boundaries to help solve local sustainability challenges, said Wake.

“In the fellowships, our students shift from theory to tackling sustainability head-on,” he said. “They are discovering how to address a complicated problem by working with people who have knowledge in different fields and integrating those approaches. It’s a skill they will take with them into their careers.”

The local impact is tangible.

Silvan Shawe, Cultivating Community’s executive director, said she was excited to see Jenkins’ project come to fruition because it will have a lasting effect.

“It will serve as a template we can use and adapt across our entire program moving forward and build a more resilient community,” she said.

By working across aisles of expertise to address local sustainability challenges, UNE and its students are providing tools and building relationships that Mainers can rely on to build resilience long after the fellowship ends.

“What we’re doing is helping to nurture and grow community,” Wake said. “Not traditionally a role that a university plays. And yet, if you asked me what UNE North is, that’s it.”